Over the past 18 months, I’ve been working on a book called The Next Episode Starts in 10 Seconds. It’s about why we keep making choices we know will harm us. From the Netflix binge that steals our sleep, to the coffee cup we toss without a thought, to the big global decisions we delay until it’s too late.

This week, I’m publishing the very first chapter. You can read it below or, if you’d rather listen, I’ve recorded it as the latest episode of my podcast Voice for the Blue.

Chapter 1 – The Loop: Why We Delay, Why It Matters

It is late. The kids are asleep, or the emails are finally done, or maybe you have just shut the front door after a long day. The house is quiet, and for the first time all day, you have space. You tell yourself one episode, then bed.

The credits roll. A countdown appears in the corner of the screen: Next episode starts in 10 seconds.

You hesitate. You know you will regret it in the morning. You know you will be tired and annoyed with yourself. Before you have even made the decision, the new episode is playing, and you are sinking back into the sofa.

That is my guilt. Netflix. That tiny gap between intention and action where comfort wins over reason.

Almost everyone has their version of this.

Maybe it is the takeaway coffee you grab on the way to work, telling yourself you need it though you know you could wait. £4 gone, another cup tossed, another small step toward the ocean filling with waste. Maybe it is the late-night scroll on social media that steals an hour. Maybe it is the Deliveroo bag left on the doorstep when the fridge was already full. Or maybe it is the unopened Amazon box in the hallway, bought in a rush of anticipation, ignored once it arrived

Different loops, same story; comfort now, consequences later.

And here is the uncomfortable truth; that loop does not stop with us. It runs through governments that delay action, corporations that lobby for loopholes, and treaties that collapse.

Sometimes I think about my son, and how he will inherit oceans full of plastic he never touched, rainforests cut before he could walk among them, species erased before he could learn their names, and treaties he never voted on. The same wiring that pulls us toward coffee cups and credit cards also drives nations and corporations to pass the costs on to the next generation.

Geneva

In August 2025, the Global Plastics Treaty fell apart in Geneva. I wasn’t in the room, but I spoke to people who were.

One described how ambition dissolved piece by piece. Words like binding became voluntary. Targets became encouragements. Another told me the silence was worse than shouting. Delegates sat under the strip lights, flipping through pages that had been hollowed out of meaning.

The most striking part, they said, was not the chaos but the calm resolve. Delegates, though frustrated, spoke of carrying on, as though the world could wait for “next time.” One even said:

“Failing to reach the goal we set for ourselves may bring sadness, even frustration. Yet it should not lead to discouragement. On the contrary, it should spur us to regain our energy …”

It was the language of hope, but also of delay. The quiet promise of I’ll do better tomorrow, spoken on a global stage.

And it was familiar.

It was the same story I tell myself at midnight with Netflix. The same story you tell yourself with coffee, credit cards, or empty gym visits.

The Loop

When I first started researching this, my first stop was dopamine. The chemical we’re told is behind every rush, every thrill, every craving. It seemed obvious: if we’re chasing comfort, distraction, delay, dopamine must be the culprit.

But the more I read, the clearer it became that the story was different. For years, scientists thought dopamine was about pleasure. They were wrong. It’s about anticipation, the maybe.

Think about your phone. It buzzes, and your brain lights up before you even know who it is. Most of the time it’s spam or something you didn’t need to see. Yet the spark comes anyway. Even without the buzz, people check their phones dozens of times a day. One global survey found that about one in five check theirs more than fifty times daily. Our brains are most responsive when the outcome is uncertain, the same principle that keeps gamblers pulling slot machine levers, traders refreshing crypto screens at 1 a.m., or someone swiping on Tinder in case the next swipe is a match. The reward isn’t in the message, or the match. It’s in the maybe.

That craving for “maybe” isn’t just modern distraction. It is ancient survival. Our brains learned to fire at uncertainty because in the wild, uncertainty often meant opportunity or danger. A rustle in the grass could be food, or a predator. A shadow on the horizon could be a rival, or a mate. Better to hold back, to scan, to conserve energy until the risk was clear.

Evolution tilted us toward postponement, toward caution, toward drifting one day at a time. Once, that wiring kept us alive. Today, it holds us back. It makes us scroll, swipe, hesitate.

And that loop isn’t just personal. The same circuitry runs through boardrooms and parliaments. Leaders feel the same spark. Their cue does not come from a notification but from the reassurance of an advisor, or the persuasion of a lobbyist: This pledge sounds ambitious enough. This delay will buy time. The brain lights up with relief, the harder choice avoided.

And the pattern repeats. Since the first Earth Summit in 1992, more than thirty international climate agreements have been signed. Over the same period, global emissions have risen by around 62 percent. Anticipation. Safety. Forgiveness. Not yet. Tomorrow.

We are not addicted to pleasure. We are addicted to the loop, the promise of anticipation, the comfort of safety, and the reset of forgiveness.

Iceland

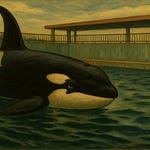

I saw the same loop in Iceland.

I was part of a team that compiled a report sent the government which reflected on hours of evidence on fin whaling: harpoons misfiring, whales thrashing for half an hour before dying, reports of pregnant whales being killed, even one case where a fetus was cut from its mother at the whaling station. We showed how some whales were shot and lost at sea, left to bleed out unseen. Alongside that, we laid out the numbers: demand for whale meat collapsing, diplomatic costs mounting, reputational damage growing.

The evidence was delivered to the fisheries minister, the one person who would decide the outcome. For weeks there was silence. Then, almost a month later, the announcement came in the papers: new whaling licences granted. The words were flat, bureaucratic, just another line in the legal register, as if lives and oceans were reduced to paperwork.

It was not defiance. It was not passion. It was clerical. Boxes ticked, signatures applied, another season allowed to begin. The message was not “whaling forever.” It was “not yet.”

Different stage. Same wiring. Pressure sparks action. Delay offers forgiveness. The story will stop later.

So, What’s This Book Is About

For a while I thought dopamine alone explained this. That was why I started writing this book, and for a time The Dopamine Dilemma was even its working title. The deeper I went, the more I realised dopamine is only the spark. What really keeps the loop alive is forgiveness. Those four quiet words: I’ll do better tomorrow.

This is the real story. The story of how humanity comforts itself with tomorrow while the clock runs out today.

This book is not about hacking habits or optimising routines. The shelves are already full of those. If the cover of this book did its job, you picked it up because you already know change has to happen, not just in the way we live, but in the systems that govern our future.

My aim is to give you two things. First, a map of the traps, from the smallest choices at home to the biggest forces shaping our planet. Second, exits that matter when the stakes are oceans, forests, and survival itself.

When I turned off autoplay on my account, it did not save the world. But it gave me back my mornings. It was a reminder that the loop can be broken. And if a loop can be broken in a living room, it can also be broken in a boardroom, at a climate summit, or in the chambers where treaties are written.

We have proof. When scientists warned that CFCs were ripping a hole in the ozone layer, governments could have stalled, delayed, said “not yet.” Instead, the Montreal Protocol banned them, and the ozone began to heal. The loop bent, and the system shifted.

If we could take back the sky, we can take back the oceans. We can take back our future.

But first we need to ask: why does the loop grip us so tightly? Why does a brain wired for scarcity now drive us to drown in plenty? That is where we go next.

This is just the start. The book will explore not only our everyday delays but also how they ripple into the biggest crises we face, climate change, biodiversity loss, and the future of the oceans.

I’d love to hear what you think. Do you see your own “loop” in it? Drop a comment below.

If you’d like to go even deeper with me, paid members will get access to the margins: the notes, the research trails and the behind-the-scenes commentary that won’t make it into the final draft. The stories themselves will always stay open, but your support helps keep them free for everyone while giving you an inside track on the journey.

© 2025 Luke McMillan. All rights reserved.

This is an excerpt from an unpublished manuscript currently in development. Please do not reproduce, distribute, or adapt this material without explicit written permission.