On Friday 13 February 2026, a wire service piece out of Australia ran the headline: ‘A surfer bitten during 4th shark attack in three days.’

The word ‘attack’ appeared seven times in that article.

In two of the four incidents, a shark bit a surfboard. Not a person. In one case, a twelve-year-old boy was bitten after jumping into the water from a cliff. He lost both his legs. I do not want to minimise that for a second. In the fourth incident, a man got minor cuts. He walked to the beach.

Four incidents. Four very different things happened. One word described all of them.

That word does something specific in a reader’s mind. It implies intent. It tells you a conscious decision was made to cause harm. If a journalist wrote that a government agency ‘attacked’ new fishing regulations, any editor would demand evidence of motive. If they described a corporation as having attacked its competitors, a lawyer would review the copy. These standards exist because imprecise language about human institutions has consequences: it distorts understanding, damages reputations, drives disproportionate responses.

When the subject is a bull shark in murky water after heavy rainfall, every one of those standards vanishes.

What is Actually Happening in the Water

Bull sharks are the species most commonly involved in bites near Sydney. After heavy rain, river runoff drops visibility to near zero. In those conditions, bull sharks rely on electroreception: they detect electrical fields generated by living organisms. A surfboard with a person paddling on it can trigger an investigatory bite. The shark is not hunting a human. It is investigating an unfamiliar object in conditions where it cannot see.

The Australian article actually mentions the murky water. It quotes a surf lifesaving official saying poor water quality favours the presence of bull sharks. The ecological context is right there in the piece. The framing ignores it entirely.

The Research is Clear

A peer-reviewed study published in Biology in 2022 examined a decade of reporting by The New York Times. Dr Chris Pepin-Neff at the University of Sydney found that between 32 and 38 percent of incidents formally classified as shark ‘attacks’ involved no injury at all. A third. Classified as attacks.

The same research found that when people believe sharks intentionally target humans, they are significantly less likely to support shark conservation. The language does not just misinform. It shapes attitudes. It shapes policy.

Some newsrooms have begun to shift. The New York Times started using ‘shark bite’ and ‘shark incident’ more frequently after 2018. California now officially classifies these events as ‘shark incidents’ in government reporting. Parts of Australia have shifted to ‘encounters’, ‘bites’, and ‘incidents’ in their government language. The science is moving. Government reporting is moving. Much of the media is still using the same word it used in 1975 when Jaws came out.

Language with a Body Count

Western Australia. Between 2010 and 2013, seven people were killed by sharks. Every death was reported as an attack. The state was labelled the ‘shark attack capital of the world’.

In January 2014, the state government deployed baited drum lines off popular beaches. Over three months, 172 sharks were caught. Fifty were shot dead. Among them: tiger sharks, a species in global decline. The programme also targeted great white sharks, listed as vulnerable by the IUCN.

The IUCN Red List assessment for great white sharks explicitly lists ‘media-fanned campaigns to kill Great White Sharks after a biting incident occurs’ as a threat to the species. Not a hypothetical threat. A documented one, identified by the world’s leading conservation authority.

I should be precise. Research into the Western Australian case found that media language alone did not directly cause the drum line policy. The connection was between public pressure and government decision-making. The media’s role was in shaping public perception over years of coverage that framed every incident as an attack, building a cumulative narrative of threat that made a lethal response seem proportionate.

The Double Standard

Newsrooms routinely describe coastal waters as ‘shark-infested’. Infested. The word we use for rats in a warehouse. Sharks have lived in the ocean for roughly 450 million years. They were there before trees existed. We are the visitors. Their home is not infested. It is inhabited.

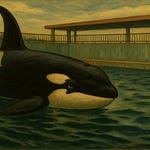

The pattern extends beyond sharks. Since 2020, orcas off the Iberian coast have been interacting with sailboats, primarily targeting rudders. Scientists studying the behaviour have described it as a possible social fad, a form of play, or learned behaviour. No person has been seriously injured. In the entire span of recorded history, no wild orca has ever killed a human being. Researchers say that if the orcas intended to destroy the boats, they could do so in minutes.

The headline word used in virtually every outlet: ‘attack’. Some go further. ‘Viciously attacked.’ An animal that has never killed a person in the wild, engaged in behaviour scientists believe may be play, described with language that implies premeditated violence. Some sailors have responded by shooting fireworks and projectiles at the orcas. This is a critically endangered subpopulation.

In every case, the word implies a conscious decision to cause harm. In every case, the evidence for that intent is absent. In every case, the framing shapes public tolerance for lethal responses.

The Cost

Oceanic shark and ray populations have declined by 71 per cent since 1970, according to a 2021 study in Nature. Three-quarters of oceanic shark species are now threatened with extinction. An estimated 100 million sharks are killed every year through fishing, finning, bycatch, and culling.

Sharks regulate ocean ecosystems from the top down. When their populations collapse, the species they keep in check proliferate. Prey species further down the chain get consumed. Habitats degrade. The fish people eat depend on healthy shark populations. This is not a problem that stays in the water. It reaches dinner tables and livelihoods.

That number, 100 million, should provoke the same response as any wildlife crisis of that magnitude. It does not. There are no telethons. No front-page campaigns. Fifty years of headlines have constructed sharks as the exception: the one animal group whose mass death feels like problem-solving rather than ecological catastrophe.

That is what the word ‘attack’, repeated millions of times across decades of coverage, ultimately produces. Not just fear. Indifference to loss.

What Should Change

I want newsrooms to treat the word ‘attack’ in wildlife reporting the same way they treat it in every other context: as a claim about intent that requires evidence.

This is not about being soft. It is about the same editorial rigour that already exists for human subjects being extended to coverage of animals whose survival increasingly depends on public attitudes. The solutions already exist. ‘Bite’. ‘Incident’. ‘Encounter’. These words describe what happened without making a claim about why it happened. They are more accurate. Researchers have been advocating for them since at least 2013. California did it. Parts of Australia did it. It just requires editors to treat one word as the editorial decision it actually is, rather than the convention it has always been.

A man paddled out on a surfboard in murky water after heavy rain. A bull shark, sensing electrical signals in near-zero visibility, bit his board. He walked away with minor cuts.

The headline called it an attack.

One word. No editorial scrutiny. Real consequences.

Ocean Rising publishes investigations, analysis, and accountability reporting on ocean governance every week.