A Struggle With What Plastic Has Created

How in many places ocean plastic has become a habitat, and what that means for conservation

The engagement on this post across numerous platforms has been staggering. From rage to bewilderment. As you sit down to read this piece, please bear in mind that this piece is a challenge. A challenge to think differently about what we call “nature” and how life adapts to our mistakes. This, I believe is critical if we are to take marine conservation seriously.

Let me know what you think!

Somewhere in the Pacific, a crab scuttles across a sun-bleached flip-flop. The foam is cracked and worn, shaped by salt and time. To the crab, it’s shelter. To the ocean, it’s structure. To us, it should be a mirror.

We like to believe plastic pollution is a problem we can fix with recycling, clean-ups, or better materials.

What if plastic hasn’t just polluted the ocean but has, for some species, become part of what they call home?

It’s becoming a foundation. A building block for marine life. A new layer in Earth’s story.

This is accidental terraforming.

Terraforming (verb): changing a planet’s environment so it can support life. Usually used in science fiction to describe turning Mars into Earth. This time, it happened the other way around. We turned Earth into something else.

The Plastic Fossils of the Future

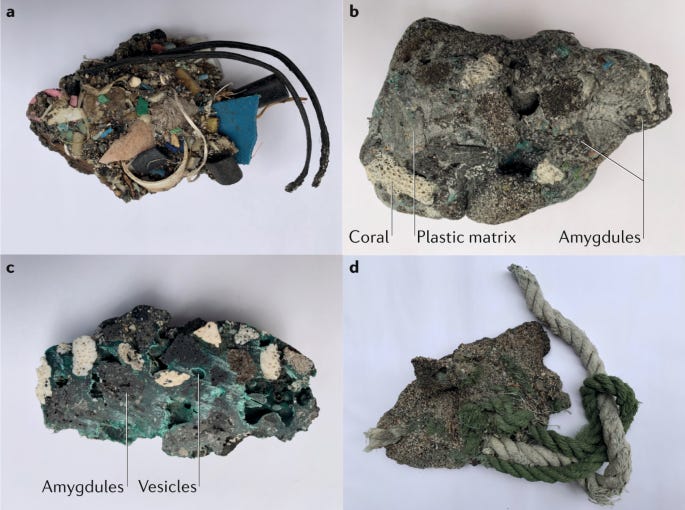

In 2014, scientists found strange rocks on a remote Hawaiian beach. They were called plastiglomerates, chunks of plastic melted into stone, coral, sand and ash.

They weren’t just bits of rubbish. They were new kinds of rock. Proof that plastic has entered the planet’s geology.

Plastic is entering what geologists call deep time, the kind of forever we measure in ice ages, not years. It's like graffiti scratched into the skin of the planet, set to outlast cities, languages, maybe even our species.

The Plastisphere: An Accidental Ecosystem

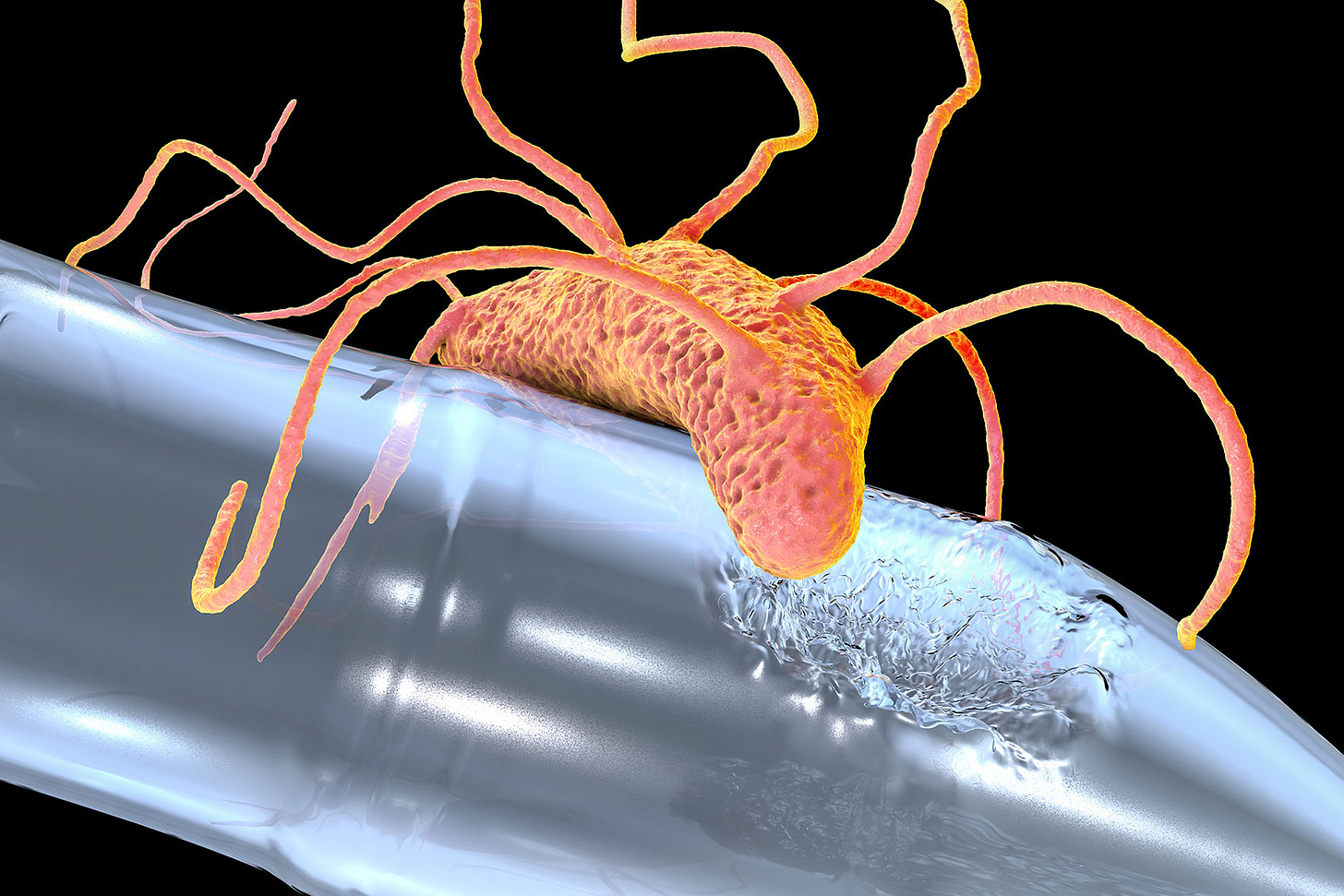

Plastic in the ocean doesn’t stay clean. It becomes alive.

On the surface and deep underwater, plastic is colonised by life. Bacteria grow on it. Algae spread over it. Viruses hide inside it. Tiny animals feed and breed on it. Scientists now call this the plastisphere, a living community built on plastic.

In one study, scientists found that plastic washed up on Canary Island beaches had high levels of these bacteria after just seven days. It suggests that plastic is becoming a growing platform for life.

Microbes That Eat Plastic

Some tiny organisms don’t just live on plastic, they feed on it.

One type of bacteria, Ideonella sakaiensis, breaks down the plastic used in bottles. A marine fungus, Parengyodontium album, digests foam and insulation. Other bacteria found on plastic waste are evolving to survive on multiple types of plastic.

They don’t erase plastic, they reshape it. What was once packaging becomes food, and then something new.

As plastic breaks apart, it doesn’t disappear. It transforms.

Bottles become pellets. Pellets become fibres. Fibres become dust.

These fragments drift into every layer of the sea. They sink into sediments. They embed in plankton, the base of the food web. They wedge into fish gills, line the guts of zooplankton, and cling to coral polyps like synthetic pollen.

What the Ocean Looks Like Now

We thought we knew what habitat looked like, but look a little deeper and you’ll see things happening.

Now, a seahorse wraps its tail around a cotton bud, thinking it’s seaweed. A turtle lays its eggs in shredded rope. A fish guards its nest under a plastic crate.

When Cleanup Becomes Collapse

We often think of cleaning the ocean as a no-brainer. Remove the plastic. Restore the balance. Job done. Only now, we might need to be more nuanced in our thinking.

Why?

It could damage habitats.

Marine animals have begun to depend on crates, ropes, bottles. Fish nest under them. Corals grow on them. Crabs hide in them. Removing plastic removes shelter.It could erase ecosystems we haven’t studied.

The plastisphere may host unique microbes found nowhere else. If we remove the plastic, we could wipe out entire new biomes before we understand what they are.It could disrupt evolution in progress.

Biofilms on plastic are hotspots for rapid evolution. Bacteria are trading genes in real time. This is risky, but it might also reveal tools for surviving future climate stress. Removing the plastic now is like shutting down a lab mid-experiment.It imposes our definition of nature.

If our waste has become someone else’s home, is it ethical to erase it? Who decides what counts as “natural”?It repeats the same mistake.

We polluted the ocean without asking what it needed. Now we want to fix it, still without asking what’s already there. If we insist on restoring purity, we might destroy the lives that adapted to the ruins.

Let’s be clear. Plastic has caused untold harm.

A significant part of my career has been spent campaigning to end plastic pollution and supporting those on the ground who are collecting ocean-bound plastic.

Ocean plastic has entangled whales, suffocated seabirds and altered ecosystems on every continent. Alongside noise, chemical runoff, climate change and overfishing, it is slowly killing the ocean.

The reason I wrote this controversial piece, is not to negate the horrific impact of plastic pollution, but to follow a thread of thinking I struggle with…

If we ignore the life we didn’t mean to create, are we still protecting nature?

If a forest burns, and new saplings start to grow in the ash, we don’t celebrate the fire. We still mourn the trees. We fight to stop the next one, but we also track what regenerates, because it shapes how we restore and protect the ecosystem long-term. That’s how I see the plastisphere. Not good, not right, but real and therefore something conservationists must factor in.

If we want to plan serious, long-term marine conservation, we have to understand all the moving parts, including the ones no one wants to talk about. Including even the fact that some life is now tangled in plastic not as victim, but as host.

Geneva’s Moment

From 5 to 14 August 2025, world leaders will meet in Geneva to finalise a historic agreement, the United Nations Plastics Treaty. It’s the most ambitious attempt yet to curb plastic pollution. Many of my colleagues and friends will be there. Some of the brightest minds of our time. The Treaty calls for bans, taxes and a circular economy. It centres fairness and it echoes Sustainable Development Goal 14, “Life Below Water”, the UN’s global target to protect marine ecosystems.

I wonder if anyone will talk about the the plastisphere.

The treaty is built on the idea that plastic must be removed. Not studied. Just cleared.

In practice, the treaty assumes that once we take away the plastic, the ocean will heal. Life will return to how it was. Things, however, might not be that black and white.

If the treaty proceeds with a default assumption that all plastic must be removed from the ocean, then we risk enacting a well-meaning policy that could inadvertently damage ecosystems already forming in its wake.

Before we remove, we must first assess.

There is an urgent need for pre-removal mapping and analysis of sites where plastic debris has become the foundation for ecological structures. This includes coral growing on synthetic fishing lines, anemones clinging to crates, or juvenile fish sheltering among submerged packaging. In such cases, indiscriminate removal could collapse microhabitats that now support vulnerable or even endemic species. A relocation protocol may be necessary for some sites, a conservation step that ensures life built on plastic is not erased along with the material itself.

This logic extends beyond the visible.

Microbial communities, including bacteria, viruses, and extremophiles, have been shown to colonise and evolve on marine plastic surfaces. The plastisphere could contain novel genetic material, enzymes, and interactions we do not yet understand. Before mass clearance operations begin, it would be prudent to collect, sequence, and bank microbial samples from key sites. This is not only a matter of scientific curiosity, but of futureproofing. We do not know what resilience, risks, or medical potential may be contained within these emergent communities.

Marine conservation has long demanded precaution. That principle should now apply to our response to synthetic ecosystems too.

The Seas Don’t Wait

A single crate, half-buried in silt. Coral growing. Fish nesting. New life taking root. Not natural. Not wrong. Just here.

The seas are not waiting for us to clear the plastic, they are already building something new. In the ocean, plastic is no longer just debris. We didn’t just pollute the ocean. We colonised it, and now we must decide what kind of stewards we want to be.

Picture this. Its 2050, a diver drifts past a reef of bottle caps and rope, covered in coral, alive with colour. She logs the coordinates, marks it as “sensitive habitat,” and moves on. She never asks who built it.

As world leaders gather in Geneva to sign a treaty that could erase this accidental life from the ocean, the question to ponder is:

Does the UN Plastics Treaty need to look deeper?

If this story bewildered or enraged you, feel free to comment. I want to know how this article makes you feel.

You can also subscribe to Ocean Rising to get weekly dispatches from the deep.

– Luke

📌 PS: If this shook you, don’t let it stop here. Repost. Restack. Remind someone that the ocean still turns, for now.

Very interesting perspective. Thanks for writing this. I hope you are able to raise this as a point in Geneva.

This is such a fascinating perspective & one I need to continue mulling over, thank you for writing this. While the 'new upstarts' of support that marine pollution can provide may offer a new matrix of life to consider, my sense is that the rally cry to clean the ocean is because the pollution is harming today's marine life in such a profound way that most of the experts for various different species and ecosystems are all sounding the alarm.

It seems like for at least the next several decades (until we get a handle on the issue) cleanups and interception of the problem (pollution) is one of the only near term solutions we all must promote given the amount of pollution being dumped in the ocean is monumentally increasing in the short term.

Removing that as quickly as possible seems to make very good sense to me as it would seem to provider greater chances for our (current marine life mix) sea turtles, whales, fish, sea birds, and ecosystems to reduce the chance for ingestion; and this applies to us humans too! It feels like the upstart marine life minority that may be 'supported' by pollution is not necessarily worth putting the current ocean food web at risk. There is so much to consider here and this is a fascinating topic, thank you.