The Mountains Beneath the Ice

How Antarctica’s hidden peaks reveal a quieter, older resilience

The peaks have no names that most people would recognise. They rise from the Sør Rondane range in Dronning Maud Land, a stretch of East Antarctica so remote that the nearest research station is Belgian. For hundreds of thousands of years glaciers have flowed around and over these summits, burying most of their flanks. As the ice thins, more rock is exposed to air and sunlight than at any point since long before humans built cities. Dark rock breaking through white. The spines of a fossil creature waking up.

Scientists expected bare stone. They found an iron factory.

Dr Kate Winter led the team from Northumbria University that analysed rocks and sediments from these nunataks, the Inuit word for peaks that pierce the ice sheet. The samples came back with iron concentrations up to ten times higher than anything previously recorded on the continent. Ten times. In a region where iron is the limiting nutrient for most phytoplankton growth, this is not a footnote. It is a revelation.

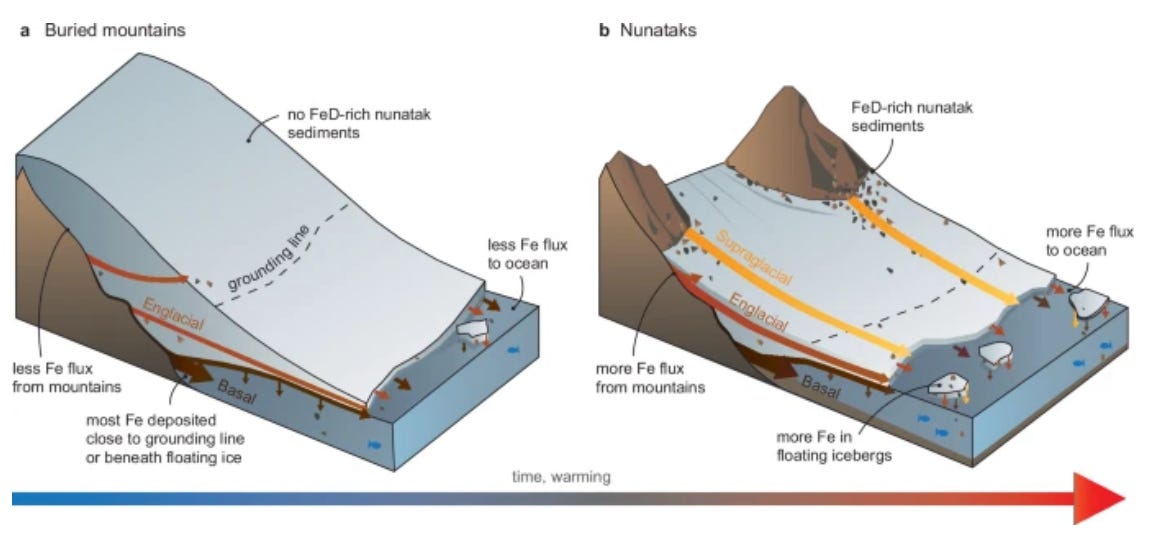

The mechanism is a simple one. Dark rock absorbs sunlight more efficiently than ice. Even in subzero air temperatures, that absorbed heat fractures the surface. Grains shatter and fall. Glaciers carry them toward the coast. Icebergs calve and drift north, shedding their cargo into the sea. The iron dissolves. Phytoplankton bloom. The tiny plants draw carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and, when they die, sink toward the seafloor, carrying that carbon into the deep.

Schematic diagram depicting sediment and iron (Fe) transfer through Antarctic glacial margins.

A mountain becomes a lung.

The timescales are staggering. A single fragment of iron-rich sediment may spend ten thousand years travelling from peak to ocean. Some journeys take one hundred thousand years. The iron reaching Antarctic waters today began its journey when woolly mammoths still walked the northern steppes. The iron released this decade will arrive in an ocean none of us will live to see. Dr Winter is clear on this point. The process will not counteract climate change on timescales relevant to human society. It is far too slow.

The point is not speed. The point is that the process exists at all.

The Architecture of Ocean Life

The Sør Rondane Mountains stretch roughly two hundred and twenty kilometres across East Antarctica. Some peaks exceed three thousand metres, towering nearly as high as the great Alpine summits. These are not small features. They are the bones of the continent, and their slow erosion has been feeding the Southern Ocean for longer than our species has existed.

Offshore, the pattern repeats in a different key. The waters south of the polar front are studded with seamounts, the great underwater volcanoes that rise from the abyssal plain like drowned cathedrals. Scientists recently mapped a chain of eight between Tasmania and Antarctica. The tallest stands about fifteen hundred metres from base to summit. Higher than Ben Nevis. Higher than Snowdon by almost half a kilometre. Four of these volcanoes were entirely unknown before the survey. They had never been seen, named, or charted. They had simply been there, in the dark, for millions of years.

Seamounts matter because they create oases. Deep currents strike their flanks and deflect upward, carrying nutrients from the abyss into sunlit waters. Phytoplankton bloom. Zooplankton follow. Fish gather. Corals anchor themselves to the rock and filter the passing water. Sponges grow in forests. Sharks patrol the slopes. Whales pause on their migrations to feed. A single underwater mountain can support an ecosystem as rich as a coral reef, invisible from the surface, unknown to almost everyone alive.

The iron mountains and the seamounts are two expressions of the same principle. Mountains feed life. On land they trap moisture and create rivers. Underwater they create upwelling and allow species to thrive in waters that would otherwise be desert. In Antarctica they do something quieter still. They donate iron to a sea starved of it. They fertilise the waters that grow the krill that feed the whales that fertilise the waters again.

The system turns. It has always turned. The question is whether we will let it continue.

The Whale Pump

Before industrial whaling, the great whales of the Southern Ocean numbered in the hundreds of thousands. Blue whales. Fin whales. Humpbacks. Sperm whales. Rights. They fed on krill at depth and defecated at the surface, releasing plumes rich in iron and nitrogen into the sunlit zone. Each whale was a vertical conveyor belt, lifting nutrients from the deep and scattering them where phytoplankton could use them.

Scientists call this the whale pump. Its scale, before we broke it, was immense. Recent estimates suggest that pre-whaling baleen whales were recycling around twelve thousand tonnes of iron each year across the Southern Ocean. Their removal did not simply reduce whale numbers. It reduced the ocean’s capacity to feed itself. It reduced the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon. The collapse of whale populations was a collapse of nutrient cycling disguised as a fisheries statistic.

The recovery, where it has been allowed to happen, offers a glimpse of what restoration looks like. Global humpback numbers fell to just a few thousand animals at the peak of industrial whaling and have since rebounded to around one hundred and thirty thousand worldwide, including roughly eighty thousand in the Southern Hemisphere. Fin whales are returning to Antarctic waters in large feeding aggregations that had all but disappeared for decades during the whaling era. Each returning whale is a nutrient pump switching back on. Each pod is a small act of repair in a damaged system.

The whales move iron vertically. The mountains move it horizontally. The phytoplankton convert it into carbon burial. The system is not designed. It emerged over millions of years of coevolution between rock and water and life. It continues to function wherever it is given space.

Forests of the Sea

The Southern Ocean is not the only place where natural carbon sinks operate at scale. Along coastlines around the world, kelp forests and seagrass meadows perform a similar function in shallower water.

Kelp is one of the fastest-growing organisms on Earth. Half a metre in a single day under good conditions. As it grows it absorbs carbon dioxide and locks it into tissue. When fronds break off and sink, they carry that carbon toward the seafloor. Some is buried. Some is eaten by animals that become part of the cycle themselves. The process is continuous, silent, and enormously productive.

Seagrass meadows are more efficient still. They cover less than 0.2 percent of the ocean floor. They account for roughly ten percent of all the carbon buried in marine sediments each year. A single hectare of seagrass buries carbon at two to four times the rate of a hectare of tropical rainforest. The carbon can remain locked in sediments for millennia, provided the meadows are not disturbed.

Salt marshes. Mangroves. These ecosystems trap sediment, stabilise coastlines, and bury organic carbon at rates that dwarf most terrestrial habitats. They are known collectively as blue carbon systems. They are among the most powerful climate allies the planet possesses.

They are also among the most threatened. Historically, seagrass meadows have been lost at rates of up to seven percent per year globally. Mangroves are cleared for shrimp farms and coastal development. Salt marshes are drained and filled. Kelp forests are collapsing in warming waters from Tasmania to California. Each loss is a double blow. The stored carbon escapes. The capacity to store future carbon disappears.

The Antarctic mountains offer iron to the open ocean over geological time. The coastal forests offer rapid carbon burial within human lifetimes. Together they represent the spectrum of natural climate regulation. We need both. We are losing one.

The Long Game

There is a temptation to turn this story into a solution. It is not a solution. The iron from the Sør Rondane peaks will not offset emissions on any timescale that matters to policy. The whales cannot absorb what we release. The seagrass cannot bury our way out of the crisis.

What these systems offer is different. They offer evidence that the planet has not stopped working. Feedback loops remain intact. The machinery of climate regulation, assembled over billions of years, continues to turn even as conditions shift around it. The question is not whether nature can help. The question is whether we will let it.

This means protecting the waters around Antarctica from extractive pressure. The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources has debated proposals for large-scale marine protection in East Antarctic waters for years. They have stalled repeatedly, blocked by nations with fishing and resource interests. The krill fleet continues to operate. Industrial vessels vacuum biomass from waters already stressed by warming temperatures and shifting ice. The krill feed the whales that fertilise the ocean that grows the krill. Remove the krill and the loop breaks.

Consumers can choose. Omega-3 supplements derived from Antarctic krill are not the only option. Algae-based alternatives exist. Labels identify the source. Each purchasing decision is a small pressure on the economics of extraction. Enough pressure and the economics shift.

Closer to shore, the opportunities are more immediate. Seagrass restoration projects operate in British, European, Australian, and North American waters. They accept volunteers. They respond to funding. A restored meadow begins sequestering carbon within years. It supports fish, filters water, stabilises sediment. The benefits compound.

Mangrove and salt marsh conservation often depends on local decisions. Planning meetings. Land trusts. Advocacy for setbacks that allow wetlands to migrate inland as sea levels rise. The carbon held in a salt marsh can persist for centuries if the marsh is allowed to remain. Drain or develop it and that carbon escapes almost immediately.

For those who eat seafood, the choices are significant. Overfishing degrades every level of marine ecosystems. It removes predators. It disturbs the seafloor. It reduces the biomass available to cycle nutrients. Choosing certified sustainable sources, reducing consumption of pressured species, asking questions at the point of sale all contribute to the health of systems that ultimately regulate climate. The ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon depends on the vitality of its food webs. Every link matters.

Finally there is attention. Ocean issues rarely dominate public conversation. Climate debates focus on energy, transport, land. The sea is one of the planet’s largest carbon sinks, rivalling the combined uptake of all the world’s forests, yet it remains peripheral in policy and in public imagination. Talking about the ocean, sharing what is discovered there, insisting that marine protection receives the same urgency as terrestrial conservation shifts the terms. Public attention precedes political action. It always has.

A Different Kind of Hope

A hidden mountain beneath Antarctic ice is easy to overlook. No colour. No movement. No drama. Yet the discovery of these iron-rich peaks offers something rare: a reason to imagine continuity.

The next time you see a satellite image of a green bloom swirling in cold Southern Ocean water, imagine the journey that created it. A flake of iron falling from a peak exposed for the first time in ten thousand years. A phytoplankton cell dividing in response. A bloom spreading across hundreds of square kilometres. A pulse of carbon drawn from the atmosphere and carried toward the deep.

Imagine the whale arriving to feed at the bloom’s edge, then surfacing to release a plume of nutrients that seeds a second bloom. The kelp forest growing along a distant coast, fronds sinking slowly into sediment. The seagrass meadow holding mud in place, locking away carbon for centuries.

These are not separate systems. They are one system operating across every ocean, at every depth, on timescales from days to millennia. The iron mountains are part of it. The whale pump is part of it. The blue carbon forests are part of it. Each piece depends on the others. Each piece depends on the health of the whole.

The resilience of the ocean is not loud. It is quiet, patient, geological in pace. Nature is not only something that suffers. Nature is also something that endures. The hidden mountains of Antarctica are proof. They show that even in a warming world, life has its own momentum.

Our task is simple. Protect enough of the planet for that momentum to continue.

If You Enjoyed This Story

This piece today is free to all to read on the day of release, and is supported entirely by paid subscribers. Their backing allows me to spend the time researching, writing and fact-checking longform stories like this one, and to keep the Voice for the Blue podcast and ocean reporting free for everyone.

If you’d like early access, paid subscribers receive every story two weeks before general release, plus occasional behind-the-scenes updates and extended features. Your support makes independent ocean journalism possible, and helps keep these stories reaching classrooms, communities and readers who can’t afford to pay.

Become a paid subscriber to Ocean Rising today.

Thanks for stopping by.

- Luke

I love these hidden interconnectivities. Thanks for the post.

Fascinating article. I read somewhere that some of the nutrients brought to the surface by whales were then transferred far inland by salmon and then released by predation etc. This paper seems to bear that out https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07980-2