The Deep Brief #22 | 20 December 2025

Your end of week ocean intelligence, built to inform, agitate, and equip you

This week I’m doing something different.

Normally, the Deep Brief is a roundup of ocean news from around the world. Some stories, though, don’t fit in a list. Some stories are the list. What happened this week is one of those.

When I started this newsletter, I called it Ocean Rising. It was meant to be a movement. Rising up to protect the sea. A call to action. I didn’t expect to be writing about the other meaning so soon. About what happens when the ocean actually rises, and there’s nowhere left to stand.

On Thursday, 27 people stepped off a Boeing 737 in Brisbane. They were handed orientation packs explaining how to open a bank account, convert a driving licence, enrol children in school. They were granted permanent residency on arrival. They can stay forever. They can leave whenever they want and come back. They have full access to healthcare, education and welfare. They can become citizens.

They are the first climate migrants to arrive under the Australia-Tuvalu Falepili Union: the world’s first bilateral treaty explicitly designed to move people away from a country that is disappearing.

Among them is Kitai Haulapi, Tuvalu’s first female forklift driver, recently married, heading to Melbourne to find work and send money home. Manipua Puafolau, is a trainee pastor from Funafuti, settling in Naracoorte, South Australia, where several hundred Pacific Islanders already work in agriculture and meat processing. Dr Masina Matolu, is a dentist with three school-aged children, relocating to Darwin to work with Indigenous communities. ‘I can always bring whatever I learn new from Australia back to my home culture,’ she said.

Twenty-seven people. That’s the story. Twenty-seven people getting off a plane.

Except it isn’t.

The Numbers Behind the Numbers

When applications opened in June, over a third of Tuvalu’s entire population applied within four days. More than 3,000 people, from a nation of 11,000, said yes, we want this option. We want a way out.

The visa is capped at 280 per year. At that rate, it would take more than 30 years to relocate everyone who applied in the first week. By which point, according to NASA’s Sea Level Change Team, half of Funafuti atoll will be underwater at high tide.

Funafuti is home to 60% of Tuvalu’s population. In places, the land is barely wider than the road. Children play football on the airport runway because there is nowhere else. The highest point in the entire country is 4.6 metres above sea level. There is no hill to run to.

The sea around Tuvalu has risen at roughly 1.5 times the global average. Under current warming trends, daily tides will submerge half of Funafuti by 2050. Under worst-case scenarios, 95% of the main atoll goes under.

The people who will live through this are already alive. Already raising families. Already wondering whether their children will have a country to inherit.

What the Water Does

King tides hit Tuvalu every March. The lagoon spills over onto the land. Water rises through the ground itself, seeping up through the porous coral. Homes flood. Roads flood. Graves flood. On the outer islands, waves have dug up the dead and pushed them inland.

‘Even with the rising waters we have to go to work,’ says Sam, a local youth advocate. ‘We have to feed our pigs. We have to go about our day even if the water is there. We can’t do much. Life doesn’t stop. You have to keep on going.’

Climate victims are supposed to wail. To despair. Sam does neither. Just the quiet matter-of-factness of someone who has learned to live with what the rest of the world is only beginning to imagine.

The science of atoll islands is more dynamic than the headlines suggest. Research by Paul Kench, a coastal geomorphologist, has shown that atolls shift, erode in some places, accrete in others. Over the past four decades, while sea levels rose around Tuvalu at twice the global average, total land area slightly increased. Some islets grew.

Climate deniers have weaponised this research, which infuriates Kench. He does not dispute that sea levels are rising or that human emissions are the cause. His point is narrower: submersion may not be the most immediate threat.

Heat may be. Freshwater almost certainly is. Tuvalu has no rivers. The population depends on rainfall collected from rooftops and stored in poorly maintained tanks. Sea level rise is pushing salt into the freshwater lens beneath the atolls. Traditional crops like pulaka, grown in pits below the water table, are failing because the groundwater has become too saline.

The land is becoming harder to live on, year by year, tide by tide.

What the Falepili Union Actually Is

The treaty was signed in November 2023 and came into force in August 2024. ‘Falepili’ is a Tuvaluan concept meaning good neighbourliness, duty of care, mutual respect. The Australian government describes it as ‘a first agreement of its kind anywhere in the world, providing a pathway for mobility with dignity as climate impacts worsen’.

‘Mobility with dignity’.

The phrase emerged from years of Pacific islanders pushing back against how the world talked about them. Researchers have documented Tuvaluans and other islanders actively rejecting the ‘climate refugee’ label, refusing to be positioned as victims, as symbols of crisis, as evidence of Western climate guilt. President Tong of Kiribati stated publicly that his people did not want to leave as environmental refugees; they wanted training to become skilled migrants. Ursula Rakova of the Carteret Islands named her community’s relocation organisation ‘Tulele Peisa’: sailing the waves on our own.

The Falepili visa reflects this hard-won shift. Unlike most migration pathways, it has no upper age limit. It is explicitly open to people with disabilities, special needs, and chronic health conditions. It grants unlimited travel back to Tuvalu, so families can maintain ties, attend funerals, participate in cultural life. Recipients get immediate access to Medicare, the National Disability Insurance Scheme, education subsidies, family tax benefits, childcare support.

The visa treats Tuvaluans as neighbours. As people who are owed something.

The Catch

Article 4 of the Falepili Union covers ‘Cooperation for Security and Stability’. In exchange for Australia’s climate support and migration pathway, Tuvalu agrees to ‘mutually agree with Australia any partnership, arrangement or engagement with any other State or entity on security and defence-related matters’.

Tuvalu must get Australia’s permission before signing defence or security agreements with other countries. The treaty emerged against a backdrop of intensifying geopolitical competition in the Pacific, with China building influence through infrastructure investment and, in 2022, signing a security agreement with the Solomon Islands.

Some Tuvaluans see this as a fair exchange. Others see it as selling sovereignty for survival. Former Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga campaigned on scrapping the treaty entirely, calling the climate mobility element ‘dangerous’ and accusing Australia of hypocrisy for supporting climate resilience abroad while remaining one of the world’s largest fossil fuel exporters.

Tuvalu did not cause the emissions that are drowning it. Australia, per capita, is one of the highest emitters on Earth. Since signing the Falepili Union, Australia has approved seven coal mine expansions. One is licensed to operate until 2088. The Falepili Union is unprecedented, generous even, by the miserable standards of international climate policy. A deal between the desperate and the complicit.

What Will be Lost

‘Our culture is integrated, linked to land,’ says one Tuvaluan official. ‘Given the small land mass we have, any erosion, any land being taken away, that’s affecting our cultural way of living.’

Foreign Minister Simon Kofe, who famously addressed COP26 while standing knee-deep in the ocean, has spoken of the generational divide. Some elders, he says, are happy to go down with the land. Others are leaving. ‘The one thing that is clear is that the people have a very close tie to their land.’

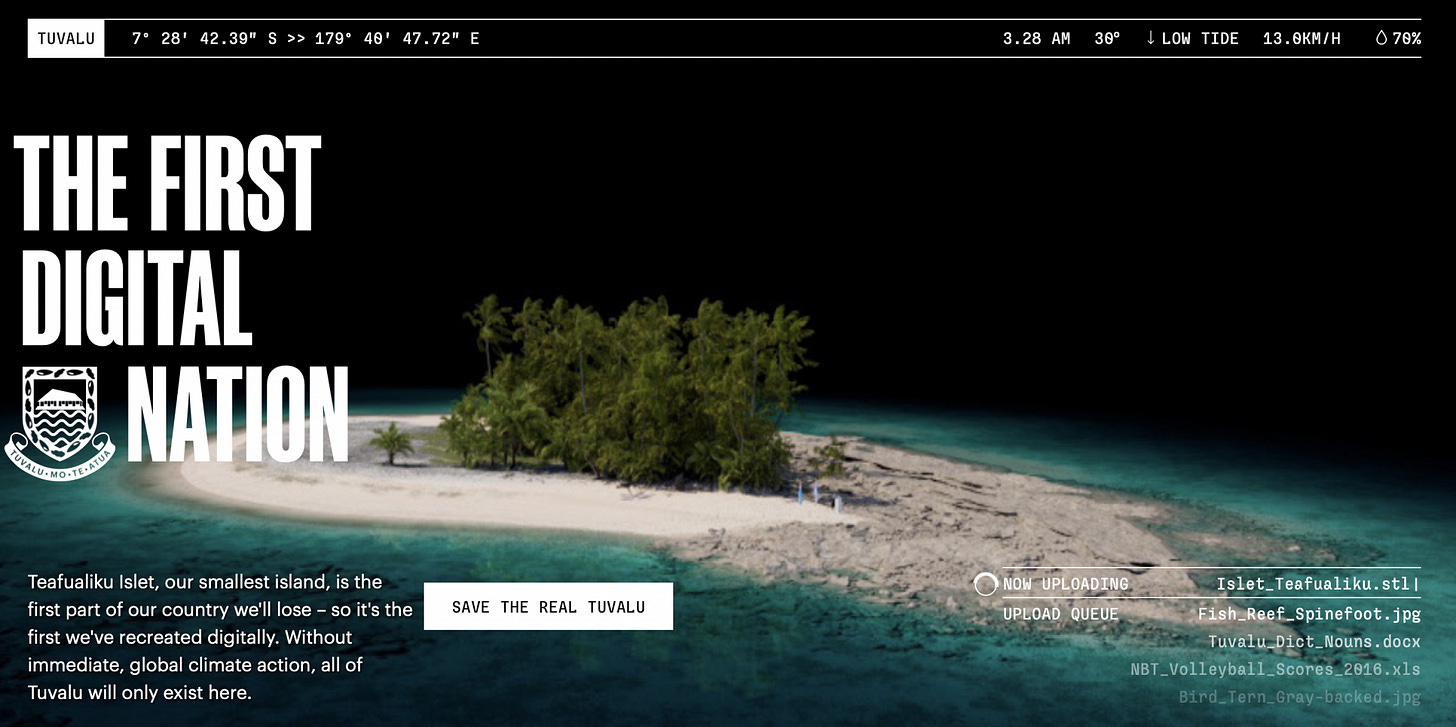

Tuvalu is now building a digital twin of itself. A replica nation in the metaverse, designed to preserve what the sea will take. Government officials speak of maintaining statehood and sovereignty even if the physical territory disappears entirely. International law has no framework for this. Nobody does. Tuvalu is writing the rulebook as the water rises.

‘What will happen to the future generations of our country?’ one resident asks. ‘This is the type of thing we think about when we say leaving Tuvalu.’

What This Means

Twenty-seven people got off a plane in Brisbane. Three thousand more are waiting. The populations of Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, and other low-lying Pacific nations are watching to see if this model works.

The World Bank estimates 216 million people could be internally displaced by climate change by 2050. The coastal communities from Bangladesh to Florida who will cross borders are not included in that figure. All of them will face some version of the same question: stay and adapt, or go and start again.

No other country can copy the Falepili Union exactly. It emerged from specific geopolitical circumstances, colonial history, and the particular vulnerability of a microstate that happens to sit in Australia’s sphere of influence. A wealthy nation can, if it chooses, create a legal pathway for climate-affected people that treats them as humans. Australia has.

Climate justice, in practice, looks like a dentist moving to Darwin with her three children. A forklift driver sending money home. A pastor serving agricultural workers in a small South Australian town.

Climate failure looks like this too. None of it would be necessary if the world had acted 30 years ago, when the science was already clear. Every climate migrant is a monument to political cowardice. Every resettlement programme is an admission that we chose this outcome.

I named this newsletter Ocean Rising as a rallying cry. Rise up. Protect the sea. Fight for it.

I’m watching that name take on a second meaning now. One I hoped would stay theoretical for longer. The ocean is rising. Twenty-seven people got off a plane this week because of it. They won’t be the last.

Tuvalu’s motto is ‘Tuvalu mo te Atua’. Tuvalu for God. Its people have a different rallying cry now, one that speaks for every Pacific island nation watching the tide charts and the visa queues.

‘We are not drowning. We are fighting.’

Stories like this one take time. The research, the voices, the context that makes 27 people getting off a plane mean something. Paid subscribers make that work possible.

Tuvalu has 11,000 people. Ocean Rising now reaches 30,000 a month. We can be louder than the tide.

Why Readers Subscribe

Early access to podcast episodes and transcripts

Monthly 5,000-word investigative reports

Exclusive Q&As and behind-the-scenes dispatches

Ad-free, independent ocean journalism

Thank you to every Founding Member and paid subscriber who makes this possible.

See you next week.

— Luke

Thank first picture by Mario Tama really communicates vulnerability Luke.