Ten Days of Warnings. Then it Exploded.

Inside the disaster that buried Sri Lanka’s coast in plastic snow

An exclusive report on the ship fire that poisoned Sri Lanka, and the global system that enabled it.

In 2021, a cargo ship caught fire off Sri Lanka’s coast, spilling hundreds of tonnes of hazardous chemicals and plastic into the sea. The owners expressed regret and offered cooperation, but stopped short of admitting legal liability. This wasn’t an oversight. It was strategy. Maritime law protected them, and they knew it.

One ship burned, but the system was already on fire.

Ten Days to Disaster

According to black box transcripts obtained and analysed by Watershed Investigations, the captain of the X-Press Pearl, Vitaly Tyutkalo, raised the alarm days after leaving Dubai. A container of nitric acid was leaking. The crew activated fire pumps. Orange vapours trailed from the base. No port would take it.

Watershed also obtained internal company emails showing repeated requests for help from Tyutkalo to his superiors. He reported the leaking, smoking, nitric acid container on day two of the journey. Ten days later, it caused the fire.

"We found already smoke, orange color, if you will read my email right. I sent to everybody, but still nobody. Already three days fire pump running, but leakage remained on deck, and maybe more and more corrosion." — Vitaly Tyutkalo, Ship’s Captain

The vessel was refused unloading in both Qatar and India. When it approached Colombo, the Sri Lankan capital, the captain again requested emergency assistance. The request was denied.

"Again. Sorry for disturbing. Yes, we have same problems smoking container, but inside cargo hold too much smoke. Smoke, very chemical, very noisy, very, I don't know, very poison. Already 10 days and still not stop leakage, still nonstop, smoke on the increase." — Vitaly Tyutkalo

For nine days, the fumes curled into the sky, unanswered.

Then, just after dawn on 20 May, heat met pressure. The deck ruptured.

Flames tore through the containers. Tyutkalo screamed into the radio.

“Fire increasing, increasing, increasing on deck...”

“Boom. Boom. Boom.”

The flames were visible from shore. Fishermen turned back. Residents evacuated. By the time the fire was under control, it was too late.

The Plastic Invasion

Beaches along Sri Lanka’s western coastline were buried in what locals called “plastic snow.” In some places, the layer was knee-deep. Local women sifted them from the sand.

The X-Press Pearl carried 1,600 tonnes of plastic nurdles, that is, 50 billion small pellets of raw plastic used to make most plastic goods. When fire ruptured the containers, many melted and fused into blackened lumps. Others spilled into the ocean.

Four years on, the pellets are still being collected. The same women return day after day, sieving the beach by hand. And tomorrow, they will still be there — the women, the sieves, the plastic that will not go away.

The most toxic nurdles are believed to remain adrift.

In collaboration with Watershed Investigations, environmental chemist Dr David Megson analysed pellets collected from Sri Lanka’s coastline over four years. His findings were damning. The nurdles were absorbing and concentrating contaminants from the water.

“The plastic pellets that are still going round appear to be sucking up more pollution from the environment and are becoming more toxic.” — Dr David Megson, Forensic Chemist

Subsequent lab tests suggested that the longer these nurdles stay in the environment, the more hazardous they become, acting like sponges for pollutants already present in the sea. These accumulating toxins could pose a long-term risk to marine life and potentially human health.

“The disaster is not over. I think it'll persist for a lifetime.” — Muditha Katuwawala, Environmentalist and Founder of The Pearl Protectors

The ecological toll is still unfolding. Dead turtles, dolphins, pilot whales and seabirds have washed ashore. Fisheries have collapsed along the west coast. No one has yet studied what this means for people’s health, for the fish they eat, the water they drink, the air they breathe.

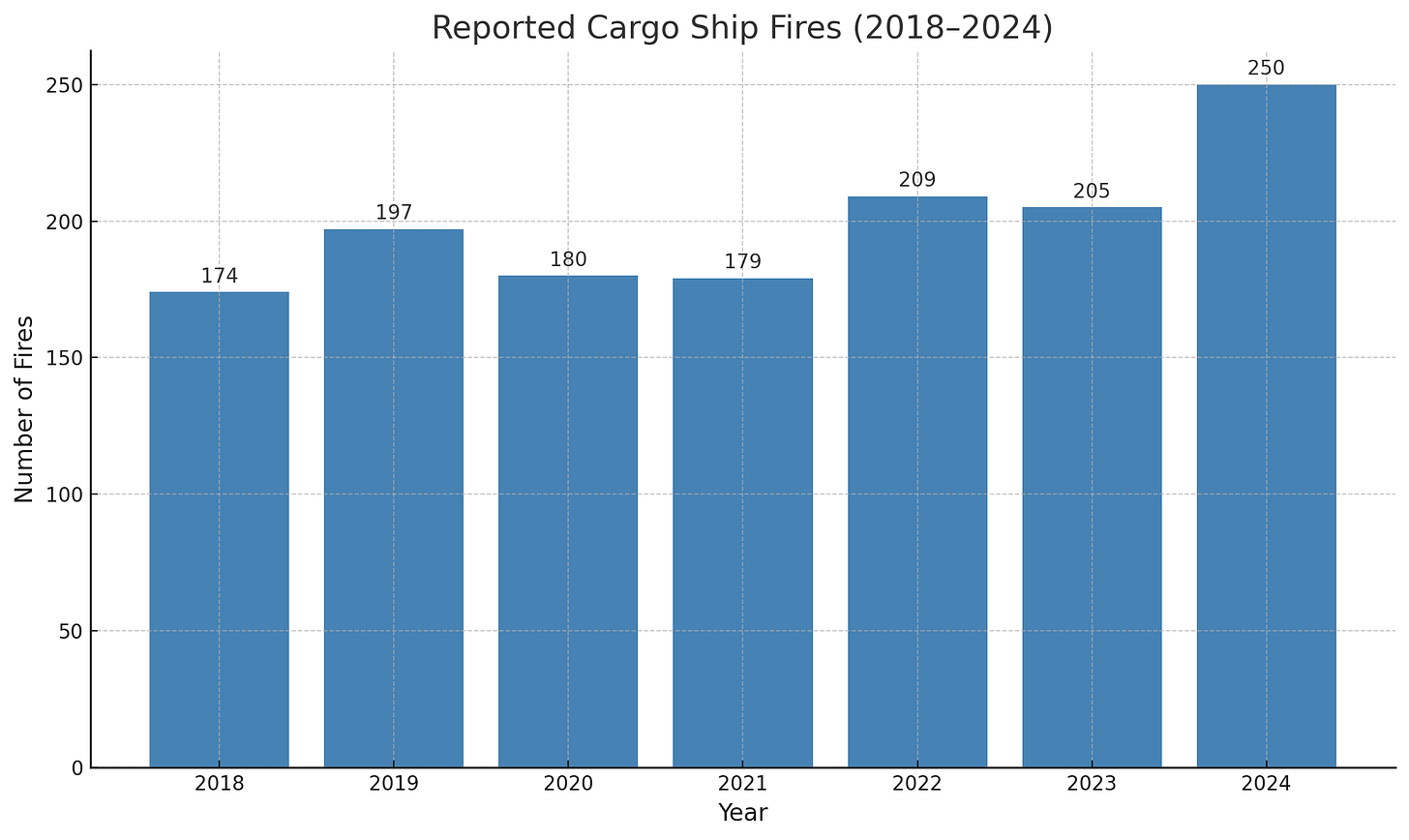

Fires at Sea: A Rising Threat

Shipboard fires have surged in recent years. Allianz Safety & Shipping Reviews recorded 174 fires in 2018, 209 in 2022, 205 in 2023, and 250 in 2024, the highest in more than a decade. In 2023, fires dipped slightly to 205. Many involved container ships, ro-ro ferries, and car carriers — vessel types vulnerable to internal combustion and battery-related fires.

A major cause: hazardous and mis-declared cargo. Lithium-ion batteries now rival charcoal as leading causes of onboard combustion. Gard and GCaptain reported in 2020 that a cargo-related fire occurred every 10 days.

The Next Pearl

In June 2025, another cargo ship caught fire. The Morning Midas, a 600-foot car carrier flagged in Liberia, was carrying 3,000 vehicles, including over 700 electric and hybrid models, from China to Mexico.

The fire broke out on 3 June, about 300 miles southwest of Adak Island, Alaska. A plume of smoke rose from the EV deck. All 22 crew members were rescued. The ship remained adrift.

On 24 June, the Morning Midas sank in waters 5,000 metres deep. It now rests on the seafloor with lithium batteries, thousands of submerged vehicles, and unknown quantities of fuel.

In 2023, a similar freighter, the MV Fremantle Highway, burned for over a week, with 3,000 vehicles on board. One crew member died. A Dutch safety board later warned of “inadequate fire response capacity” for battery-related cargo.

These are not isolated accidents. They are warnings.

The System That Enables Disasters

The X-Press Pearl disaster didn’t happen in isolation. It unfolded within a global shipping system built to obscure responsibility, deflect blame, and shield those at the top from consequence.

Here’s how it works.

More than 70% of the world’s merchant ships are registered under so-called “open registries”, countries like Panama, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands that offer tax breaks, minimal oversight and secrecy. Even ships not flying these flags, like the Singaporean-registered X-Press Pearl, still operate within the same fragmented legal architecture.

Ports turned the ship away. Insurers capped liability. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) set rules, then looked the other way.

That’s what happened to the X-Press Pearl when it sought help with the leaking nitric acid container. Qatar said no. India said no. Only Sri Lanka said yes, too late.

Shipowners are insulated by complex webs of liability insurance. Caps set by decades-old treaties mean even the worst ecological disasters may cost less than the ship’s replacement parts. The cleanup and compensation claims for the X-Press Pearl have been estimated at over $6 billion. The actual payout is expected to be a fraction of that.

A few claims are quietly settled. Most sink into years of delay. Almost none reach court. Justice is rarer still.

The IMO is the UN body meant to regulate shipping. It has no investigators, no enforcement powers, and little ability to hold anyone to account. Its rules are written down, but often ignored. I contacted the IMO several times. They eventually replied.

On liability, the IMO explained that the compensation limits set in the 1970s can be changed, but only if one of its member countries asks for a review. The last update was more than a decade ago, agreed in 2012 and applied from 2015.

On hazardous cargoes, the IMO said the X-Press Pearl case has been reviewed. A summary of lessons learned will be published, and it highlighted that the official report recommended using existing codes to handle dangerous goods more safely.

On ports turning ships away, the IMO pointed to new rules adopted in 2023. These guidelines are meant to help countries decide what to do when a ship in trouble asks to enter with hazardous cargo.

Finally, on disaster response, the IMO said it worked with Sri Lankan authorities after the fire, together with UN partners. The EU funded support efforts, and the incident has since prompted new international talks on how plastic pellets are shipped.

None of these responses change the structural reality. No global shipping court. No ocean crimes tribunal. No independent disaster board. Just rules that depend on governments to act, and processes that take years to move.

Shipping still slips through climate treaties like the Paris Agreement. It remains one of the dirtiest industries on Earth, and one of the least accountable.

What this means is simple: ships can carry hazardous waste through the world's most biodiverse waters, and if something goes wrong, the burden falls on coastal communities, not carriers.

It’s a system built for profit, not safety. For secrecy, not transparency. For growth, not the life of the ocean.

“With the volume of shipping that we have across the world and with the standards for the shipping fleet that's moving all this material, I think we should expect regular occurrences like the X-Press Pearl.” - Ian MacDonald, Professor of Oceanography, Florida State University

In Mauritius, the Wakashio spill. In Lebanon, deadly port fires. And in Sri Lanka, women with sieves, still gathering poison from the sea.

The System That Sank Accountability

“The total damage we calculated as an interim number as 6 billion US dollars.” - Professor Prasanthi Gunawardhana, Environmental Economist

For every $1,000 in damage, the shipping company has paid less than $2.

An expert committee appointed by the Sri Lankan government estimated the total damage from the X-Press Pearl disaster at $6.4 billion. This includes $4.3 billion in biodiversity losses, $1.1 billion in fisheries and livelihood damage, and hundreds of millions in healthcare, coastal restoration, and long-term cleanup costs. (Source: Pulitzer Center, 2023)

By late 2023, Sri Lanka had received less than $8 million from the ship’s insurers (Maritime Executive, 2023). Even if additional pledged or pending amounts are included, the total recovered is less than 1% of the total damage, far short of the “under 2.5%” figure sometimes cited.

In 2023, a UK court capped the shipowner’s liability at just £20 million, invoking the 1976 Convention on Limitation of Liability for Maritime Claims, a treaty that allows shipping companies to limit payouts based on the weight of the vessel, not the extent of the damage. Legal experts say Sri Lanka’s appeal in Singapore has slim prospects (Maritime Executive, Pulitzer Center).

This is a system working exactly as designed, to protect polluters and abandon victims.

“We think they don't give enough money to recover the damage they have done to our nature and to the other people.” - Dr. Ravindra Kariyawasam, Ministry Advisor

The Sea Remembers

Parts of the X-Press Pearl still lie on the seafloor off Sri Lanka. The ship broke in two. Some wreckage was removed. Much remains. Microplastics have entered fish, and toxic residues contaminate nearby waters. Heavy metals, nitric acid remnants, and plastic nurdles continue to wash ashore. Fisheries haven’t recovered. It didn’t sink into silence. It sank into people’s lungs, their nets, their daily lives.

Jude Celanta, a fisherman near Negombo, remembers the disaster clearly:

“I saw a huge ball of fire coming out of the ship, and then the beach was covered with oil, dead turtles and shipping containers. I kind of felt it was the end of the world.” “There’s no fish since then. We've never had the same amount of fish that we used to catch.”

His hands, once calloused from nets, are now idle. His son is applying for a visa to Canada.

I spoke with Leana Hosea, an award-winning environmental journalist of Sri Lankan heritage and founder of Watershed Investigations, the team that first obtained and analysed the ship’s black box transcript. Hosea’s reporting, based on leaked documents and chemical testing, helped reveal how the disaster unfolded and why no one stopped it.

“It was one of the worst environmental disasters in the country’s history,” she told me. “Yet I felt it didn’t get the coverage it deserved, because it happened during COVID, and because it happened to a small developing country.”

“With several ongoing compensation cases, there are the legal challenges and the difficulties of getting information from the shipping industry.”

“There’s now a second influx of nurdles onto Sri Lanka’s coastlines, believed to be from the MSC Elsa 3, a cargo ship which caught fire and sank off the coast of Kerala, India, on May 25, 2025. So the X-Press Pearl disaster is not one of a kind and shipping pollution is not as rare or insignificant as you might think.”

This is not just about Sri Lanka. It is about us. The laws we permit. The seas we sacrifice.

A treaty to stop plastic nurdle pollution is being drafted. Nations could mandate better fire detection. Ports could be required to accept hazardous cargo.

None of that will happen without pressure.

So long as a ship can sail under one flag, burn under another, and be buried by a third. The ocean pays. The polluters sail on.

The X-Press Pearl will not be the last. It could be the one we finally learn from.

Tomorrow, they will still be there, the women, the sieves, the plastic that will not go away.

Tomorrow, even more nurdles will wash ashore.

This investigation was published in Oceanographic Magazine, one of the leading journals dedicated to the ocean. As a writer, seeing my work appear there is a milestone moment, proof that these stories matter and deserve a global stage.

The truth is, the systems that caused the X-Press Pearl disaster are still in place. Shipping fires are rising. Liability loopholes remain. Communities are left with the damage while polluters sail on.

Paid subscribers make it possible to keep digging into these stories. For the women still sifting plastic by hand. For the seas still carrying poison. For the future we cannot afford to lose.

Sources: Allianz Safety & Shipping Review (2018–2025), GCaptain, Gard.no, Watershed Investigations, Maritime Executive, Africanews, Ersoy Bilgehan Law Office, The Pearl Protectors, Sri Lanka Government Reports, and interviews conducted June 2024–July 2025.

This story needs to be re-told and re-told. Many many stories like this and only one solution: The manufacturer needs to be responsible for , not only the product creation cost, but all the product costs from cradle to grave.

Great piece Luke and shipping remains my priority to tackle from within the NHS/healthcare. I have been presenting this topic to healthcare systems and professionals since 2021 and although we've raised awareness a little, actions have been slow. I will once again attend a day at LISW next month and try once again to get those present to understand that to harm the Ocean is to harm ourselves and without good health, we will fail.