One Percent

The world promised to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030. In the Western Indian Ocean, sharks and rays got 1%.

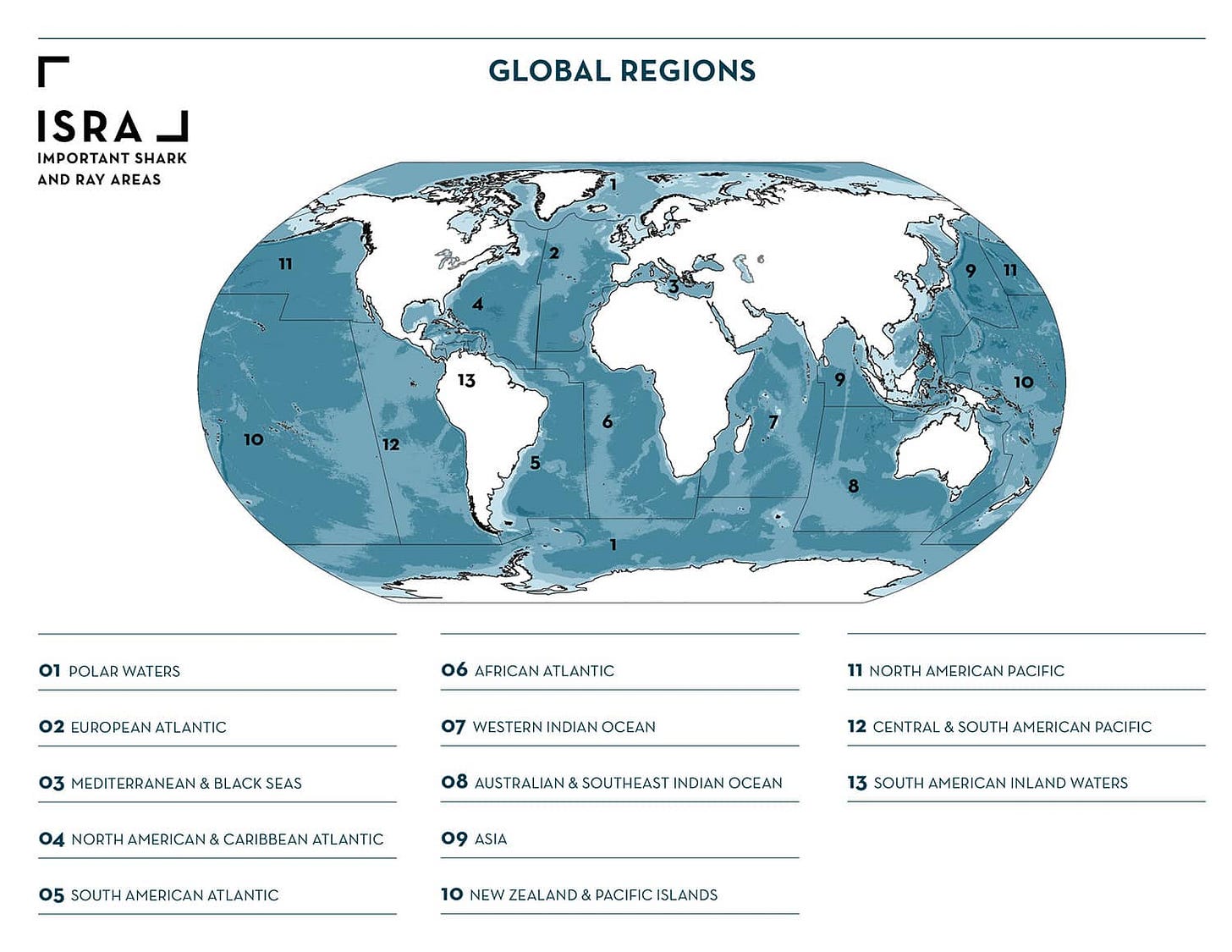

In January, a team of 237 scientists across 29 countries published the most comprehensive map ever produced of where sharks and rays live, breed, feed, and migrate in the Western Indian Ocean.

They identified 125 Important Shark and Ray Areas, covering 2.8 million square kilometres of ocean. These are not abstract conservation wishlists. They are places where threatened species are documented, right now, doing the things they need to do to survive: giving birth, feeding, resting, moving between habitats.

Then the researchers checked how much of that habitat is actually protected.

The answer: 7.1% overlaps with any marine protected area. Just 1.2% falls within fully protected no-take zones, where fishing is prohibited entirely.

One percent.

What Lives There

The Western Indian Ocean stretches from South Africa to the Red Sea, from the Maldives to Madagascar. It covers roughly 8% of the world’s ocean and is home to 270 species of sharks, rays, and chimaeras (sometimes called ghost sharks), about a fifth of all known species globally.

Almost half of them, 46%, are threatened with extinction.

Between the two comprehensive global assessments of sharks and rays, in 2014 and 2021, only three species recovered enough to have their extinction risk downgraded. All three were skates. Three, out of more than 1,200.

The Western Indian Ocean is not the only region losing species faster than science can document them. In 2023, the Java stingaree, a small ray from Indonesian waters, was declared Extinct, the first documented marine fish extinction directly linked to human activity. Two more species, the lost shark from the South China Sea and the Red Sea torpedo ray, are classified as Critically Endangered, Possibly Extinct. All three were small, geographically restricted, and lived in areas with intense, unmanaged fishing. Nobody noticed until it was too late.

What are ISRAs?

Important Shark and Ray Areas are a relatively new tool, launched by the IUCN Shark Specialist Group. Think of them as the shark equivalent of Important Bird Areas, a concept that has guided bird conservation for decades. Scientists submit evidence that a specific area of ocean is regularly used by sharks or rays for breeding, feeding, resting, migrating, or aggregating. An independent panel reviews the evidence. If it meets formal criteria, the area is designated.

ISRAs carry no legal protection. They are a map of where protection is needed, built from evidence rather than politics.

In the Western Indian Ocean, 125 areas qualified, spanning 28 of the region’s 29 national jurisdictions. Only Jordan, with one of the smallest stretches of national waters in the region, had no qualifying area.

The species documented across these areas include some of the ocean’s most recognisable animals: whale sharks, reef manta rays, scalloped hammerheads. The reef manta ray alone qualified in 34 separate ISRAs.

They also include species most people have never heard of. The eastern dwarf false catshark, whose entire known range sits inside a single ISRA. The flapnose houndshark, with more than half its range covered. Electric rays so poorly studied that over a third are classified as Data Deficient, meaning scientists do not have enough information to assess whether they are in trouble.

The Protection Gap

Here is where the study becomes an accountability document.

In 2022, 196 countries adopted a global biodiversity agreement known as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Its Target 3 commits them to conserve and manage at least 30% of the world’s marine areas through protected areas and other effective measures by 2030.

The Western Indian Ocean is nowhere close. Across the entire region, marine protected areas cover 6.4% of ocean surface. Roughly a third of that is fully protected no-take zones. The rest permits some level of fishing.

When the researchers overlaid the ISRAs onto existing protected areas, the result was damning. Only 65 of the 125 ISRAs overlapped with any MPA at all. The total overlap between ISRAs and no-take MPAs amounted to 22,201 square kilometres, and 98% of that was in a single country: the Seychelles.

For the remaining jurisdictions, the overlap was negligible or nonexistent. India, Pakistan, Yemen, the Maldives, Somalia, Sudan, Mauritius, Eritrea, Djibouti: zero overlap between identified shark and ray habitat and fully protected areas.

These governments signed the agreement. They made the commitment. The maps are new. The crisis is not. This is what delivery looks like.

Marine protected areas in the Western Indian Ocean were not designed with sharks and rays in mind. Most were created to protect coral reefs in shallow water. That is useful for some reef-associated species, but it does nothing for deep-water sharks, pelagic species migrating through open ocean, or rays that depend on estuarine and mangrove habitats.

The result is a protection system that is accidentally, rather than deliberately, conserving a fraction of what these species need.

Paper Parks

Even where protection exists on paper, enforcement is another matter.

The study references the Western Indian Ocean’s status as one of the worst regions globally for illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. A 2023 WWF analysis estimated that more than a third of fishing effort in the Southwest Indian Ocean may be IUU, representing annual losses exceeding US$142 million.

The authors note, carefully, that several no-take MPAs in the region ‘effectively serve as paper parks due to limited resources and enforcement capabilities’. The Chagos Archipelago, often cited as one of the world’s largest no-take marine reserves, has documented illegal exploitation of threatened manta and devil rays within its boundaries.

As we see around the world with protected areas, protection without enforcement is just a line on a map.

The Hidden Data Problem

One of the study’s most important findings has nothing to do with protection gaps. It is about who holds the knowledge.

Nearly half of the evidence used to identify ISRAs, 47%, came from unpublished sources: citizen science records, fish market surveys, local ecological knowledge, informal researcher observations, government datasets that never made it into peer-reviewed journals.

If the researchers had relied on published science alone, they would have identified ISRAs for only 52 of the 104 qualifying species. Half the picture would have been missing.

This matters because conservation planning typically depends on published, peer-reviewed evidence. If a species does not appear in the literature, it does not appear in the plans. The study found that the published record is systematically biased towards large, charismatic, shallow-water species: whale sharks, manta rays, hammerheads. Three planktivorous megafauna species alone accounted for 14% of all species-area combinations, despite representing less than 3% of qualifying species.

The species most likely to be missed are the ones most vulnerable: small-bodied, deep-water, range-restricted species that nobody is studying because they are not photogenic, not commercially valuable, and not visible from a dive boat.

Only 12% of the region’s deep-water species had enough data to qualify for an ISRA. Almost all of that data came from fisheries, the very activity threatening them.

What Needs to Change

The paper frames ISRAs as a tool that could help governments meet their 30x30 commitments. The data is there, the maps exist, the evidence has been gathered, reviewed, and published.

What is missing is political will.

The Convention on Migratory Species passed decisions in 2024 requesting parties to incorporate ISRAs into spatial planning and conservation action. Twenty-two Western Indian Ocean countries are CMS parties. The mechanisms exist.

The high seas treaty, formally the Agreement on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction, was adopted in 2023 and entered into force in January 2026. It allows for the designation of marine protected areas in international waters. Two-thirds of the total ISRA area in this study sits in those waters, currently with no protection whatsoever.

For countries looking for a practical path to meeting Target 3, ISRAs offer a ready-made evidence base. Amsterdam and Saint Paul Islands, Oman, and South Africa are specifically flagged as jurisdictions with high potential to meet their commitments by protecting identified shark and ray habitat.

The question is not whether we know enough. We know more than enough. The question is whether that knowledge will translate into action before the window closes.

Why This Matters Beyond Sharks

Sharks and rays are not a niche concern. They are a measure of whether ocean governance is real or performance.

Oceanic shark and ray populations have declined by 71% since 1970, according to research published in Nature. A 2024 reassessment of all 1,199 species, published in Science, confirmed they are now the second most threatened vertebrate class on the planet, after amphibians. This is a group that has been swimming the oceans for over 400 million years, predating trees, dinosaurs, and most of the life forms we consider ancient.

The systems failing them are the same systems failing the ocean: fragmented governance, under-resourced enforcement, commitments made in conference halls and abandoned at sea.

This study does not just map where sharks live. It maps the distance between what governments promised and what they delivered.

One percent protection. Four years until the 2030 deadline.

The ocean is keeping score.

This is what Ocean Rising does. The research others summarise, I investigate. The commitments others report, I track. Paid subscribers get the accountability journalism that follows the evidence wherever it leads.

References and Further Reading

The study: Cochran, J. E. M., Charles, R., Temple, A. J. et al. (2026). ‘Only One Percent of Important Shark and Ray Areas in the Western Indian Ocean Are Fully Protected From Fishing Pressure.’ Ecology and Evolution, 16(1), e72690. Open access.

Interactive ISRA map: sharkrayareas.org/e-atlas

Global shark and ray decline: Dulvy, N. K., Pacoureau, N., Matsushiba, J. H. et al. (2024). ‘Ecological Erosion and Expanding Extinction Risk of Sharks and Rays.’ Science, 386(6726). The paper that documented a 50% population decline since 1970 across all 1,199 shark and ray species.

Oceanic shark decline: Pacoureau, N. et al. (2021). ‘Half a Century of Global Decline in Oceanic Sharks and Rays.’ Nature, 589, 567-571. The earlier study documenting a 71% decline in oceanic species specifically.

Java stingaree extinction: The IUCN’s Red List assessment of the Java stingaree (Urolophus javanicus), declared Extinct in December 2023. Coverage from Charles Darwin University.

The 30x30 commitment: The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (2022), Target 3.

The high seas treaty: The BBNJ Agreement, adopted June 2023, entered into force 17 January 2026.

IUCN global shark assessment: Jabado, R. W. et al. (2024). IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group Global Status Report. The comprehensive report covering threats and conservation priorities for all 1,266 chondrichthyan species across 158 countries.

Mongabay coverage of this study: Schneider, V. (2026). ‘Critical Shark and Ray Habitats in Western Indian Ocean Largely Unprotected.’

Such a great post, it’s such a shame that we can’t seem to build political consensus on something as critical as protecting sharks which ultimately help protect the ocean. Great piece, very thought provoking

Reaching the 30×30 target — can feel almost impossible when viewed through today’s lens of fragmented governance, underfunded enforcement, competing economic interests, and the accelerating impacts of climate change. While political commitments have multiplied, effective protection still lags far behind ambition. Yet impossibility is often a function of inertia rather than feasibility — and 30×30 remains achievable if global focus shifts rapidly from designation to delivery, from promises to enforcement, and from isolated national efforts to coordinated, science-led ocean governance at scale.