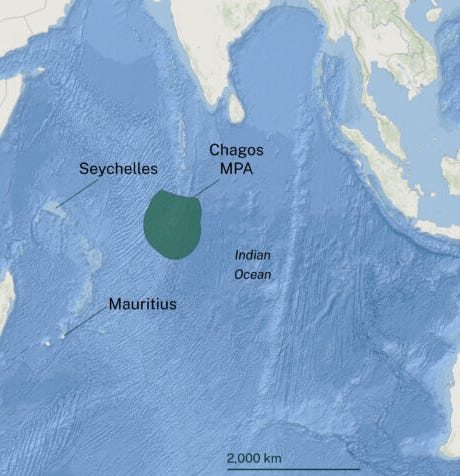

Inside the 640,000 km² Ocean Sanctuary on the Brink

The rare case where political borders match nature’s design and the clock is running out

Satellite tags reveal that the Chagos Marine Protected Area shelters turtles, manta rays and seabirds in almost exact alignment with their movements. Within weeks, its borders could be redrawn as control shifts from the UK to Mauritius, a political handover that could open one of the ocean’s rare true sanctuaries to longline fleets and anchored fishing boats.

A hawksbill turtle leaves the reefs of the Chagos Archipelago under cover of night. Above her, a red-footed booby cuts low against the trade winds. Somewhere below, a reef manta spirals upward through plankton-rich water.

All of them are moving inside an invisible border, a line on a map that has kept these waters safe for over a decade. None of them know it is one of the largest marine protected areas on Earth. Yet almost every move they make is within its boundaries.

Last week, those movements became the focus of a landmark study in the Journal of Applied Ecology. Over nine years, researchers tracked 302 animals, hawksbill turtles, reef manta rays and three seabird species, to answer a question that has divided scientists, conservationists, and policymakers for more than a decade.

Do very large marine protected areas actually work for mobile species?

The short answer from Chagos, is yes, when the design mirrors the ecology it’s meant to protect.

Tracking 300 Animals Across 640,000 km²

The Chagos Marine Protected Area spans 640,000 km² of no-take ocean, roughly the size of France and the UK combined. It was established by the UK in 2010.

Between 2015 and 2024, scientists fitted satellite tags to 22 hawksbills, 23 reef mantas and 257 seabirds (red-footed boobies, brown boobies, wedge-tailed shearwaters).

The results were striking:

95.3% of tracked individuals stayed entirely within the MPA for more than 99% of the time they were monitored.

Hawksbill turtles fed on deep reefs more than 30 metres down.

Manta rays foraged along submerged banks and atolls.

Seabirds ranged from coastal waters to the deep pelagic zone, yet most trips began and ended inside the MPA.

The Problem with “100,000 km²”

In conservation policy, the term very large marine protected area (VLMPA) applies to any no-take zone above 100,000 km², an area about the size of Iceland. It is a useful category for tracking global progress, but the number itself has taken on an unhelpful life of its own.

For governments chasing the UN’s ocean protection targets, the easiest way to score a “VLMPA” is to draw a single boundary around a vast, remote patch of ocean with minimal fishing or industrial pressure.

The Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument (PRIMNM) is one example. Expanded to more than 1.2 million km² in 2014, it made headlines as the largest protected area in the world. Yet much of it covers deep water with little to no commercial fishing, while nearby, heavily exploited tuna grounds remained unprotected. On paper, it’s a breakthrough. In practice, it’s a token gesture, protecting low-risk habitats while leaving contested, biologically rich waters open to exploitation, because it is politically easier to draw lines in empty seas than to regulate the busy, high-value zones where protection is most needed.

The Chagos data shows why this matters. When researchers modelled a 100,000 km² version of the MPA, hawksbill turtles and manta rays remained well protected (94% and 97% of tracked locations). However, seabird coverage dropped to 59%, with nearly half their foraging trips falling outside the smaller boundary. In other words, “very large” can still be too small if the design ignores where species actually go.

Political Fragility

In 2016, marine policy experts Peter Jones and Elizabeth De Santo warned that the biggest marine sanctuaries can fail the fastest. Their research, published in Marine Pollution Bulletin, showed that political shifts, changes in sovereignty, leadership, or even a single minister’s priorities, can erase years of protection in one move.

The Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument seemed to prove their point when, earlier this year, a single presidential signature from Donald Trump authorised commercial fishing across 1.27 million km² of protected waters. However, this week, in a rare reversal, a federal judge in Hawaii ruled the rollback illegal. The decision reinstated full fishing bans, safeguarding some of the planet’s most intact coral reefs, high densities of apex predators and critical habitats for endangered species. It also upheld the cultural rights of Pacific Island communities, affirming that the law requires their voices to be heard before protections can be dismantled.

Such victories are exceptional. In most cases, once protections are weakened, they do not return.

That is the fragility facing Chagos. Sovereignty is passing from the UK to Mauritius, with boundaries, no-take rules, and enforcement capacity still undecided.

The latest science shows this 640,000 km² MPA works for turtles, mantas and seabirds. Yet within weeks of the handover, nesting beaches undisturbed for decades could see longline fleets anchored offshore, their decks strung with hooks and nets.

Lessons from Chagos

What makes Chagos different is the rare case where a political border happens to fit the natural one, covering habitats from shallow feeding grounds to deep pelagic waters. That is not the norm.

It’s also a glimpse of what the UN’s 30×30 pledge could deliver if more MPAs were designed this way, rather than chasing numbers with poorly placed boundaries.

Under the UN’s 30×30 pledge, more than 190 countries have committed to protecting 30% of the planet’s land and ocean by 2030. Today, only 8.6% of the ocean is protected, and just 2.7% is strongly protected, leaving a long way to go. The rush to meet that target has driven a boom in very large MPAs, but many are “residual,” vast yet poorly located, failing to cover the habitats species actually use.

Chagos shows it can work, but only with:

Careful site selection based on multi-species tracking and habitat data

Long-term funding for enforcement

Political frameworks that survive changes in leadership or sovereignty

The Question Ahead

In the coming months, decisions made in meeting rooms thousands of miles from the Chagos reefs will set the course for decades. They will decide whether nine years of tracking data becomes a living blueprint for how to protect mobile ocean life, or a record of what we once had.

If the MPA endures, it could stand as rare proof that conservation can keep pace with creatures that cross thousands of kilometres in a single season. If it unravels, it will not just be a missed opportunity. It will be the dismantling of one of the last places on Earth where marine protection truly works. The longline hooks will come first. Then the empty beaches. The silent seabird colonies. The mantas spiralling upward for the last time before vanishing into unprotected water.

The choice will be made quickly, but its consequences will last for generations.

If you’re a paid subscriber, thank you. You care about truth in ocean reporting, that’s why you’re here. You’ve helped make this kind of deep reporting possible, this article might not exist without you, and you’ve read it before anyone else.

If you’re reading this two weeks after release, I’m glad you found it, but imagine not having to wait for the next one. Paid subscribers get early access to every major investigation, plus bonus stories and behind-the-scenes reporting notes that never make it into the free edition.

Your subscription keeps stories like this from disappearing into closed research paywalls or gathering dust in government reports. It ensures they reach the people who can act on them.

If you’d like to support this work and be first to know what’s happening in the ocean before it makes headlines, you can upgrade in just a few clicks. It keeps Ocean Rising free for those who can’t pay, and keeps these stories flowing.

Sources

Hays, G. C. et al. (2024) “The effectiveness of a very large marine protected area for highly mobile megafauna.” Journal of Applied Ecology.

Jones, P. J. S. & De Santo, E. M. (2016) “Is the race for remote, very large marine protected areas taking us down the wrong track?” Marine Pollution Bulletin.

UNEP-WCMC & IUCN (2024) Protected Planet Report 2024.

United Nations (2022) Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.