Harpooned: The Great Whale Betrayal

A covert mission exposes the truth behind Norway’s modern whaling industry

A new film, Harpooned: The Great Whale Betrayal, forces us to confront what happens in northern waters most of us will never see. Produced by the Endangered Species Protection Agency (ESPA) after months of covert operations, the documentary captures the reality of modern commercial whaling with precision and restraint.

I worked closely with the ESPA team before their deployment. Their professionalism and discipline were remarkable. This was not activism for spectacle. It was evidence gathering, methodical, lawful, and forensic.

The team operated from a remote coastal base in northern Norway, one of the most hostile marine environments on Earth. For weeks, they shadowed whaling vessels from international waters, documenting every sequence on camera with timestamps, GPS coordinates, and visual corroboration.

“Harry Taylor and I, 11 years ago, founded the Endangered Species Protection Agency to protect not only the species themselves but the wildlife custodians that look after them. It’s it’s a difficult operation to film the Norwegian whalers but it it’s got to be done. Just because it’s difficult it doesn’t mean it should be left alone.” - Peter Carr, Co-Founder, ESPA

They could not interfere. They could only watch. Norwegian regulations stipulate that death should be instantaneous. The reality captured on film tells a very different story.

What they Documented

The purpose of the footage was to record existing practices, reveal suffering, and build a bank of evidence for ongoing welfare investigations. The film captures on camera what has long been reported by welfare scientists but rarely seen by the public.

Prolonged deaths

The footage shows whales struggling for extended periods after being struck. It is well known that every year minke hunts sometimes require multiple harpoon strikes on individuals. Official Norwegian data report an average “instantaneous death rate” of 80 to 85 percent, yet independent experts have long questioned both the definition of “instantaneous” and the reliability of self-reported data.

“It’s always bad to see a whale killed and I can’t help but look at their eye. I mean, that whale was wounded. It didn’t take long to die, but it was a horrific death” - Peter Carr, Co-Founder, ESPA

Intergovernmental reviews show that when whales do not die instantly, their deaths can last for many minutes. Investigations have recorded cases exceeding twenty minutes from strike to death. These figures rely almost entirely on self-reporting, highlighting why independent monitoring is essential for any meaningful welfare assessment.

A Conflict of Interest

The veterinarian responsible for advising on whaling welfare standards has also been identified as a patent holder for the Whalegrenade-99, the explosive harpoon grenade used by Norwegian vessels. The overlap between welfare oversight and financial interest has been publicly reported and raises an obvious conflict of interest. Norwegian authorities have not publicly addressed the issue.

“Imagine a pharmaceutical regulator approving drugs they personally profit from,” says Dr Ingrid Visser Brakes, cetacean welfare expert. “The public would be outraged. Yet in Norwegian whaling this arrangement has persisted for years without meaningful reform.”

The End of Independent Oversight

Norway removed its “Blue Box” electronic monitoring system in 2022. These devices once recorded kill times and provided an independent record of compliance. Their removal created a transparency gap. Today, whalers report their own data with no continuous third-party verification. Animal welfare organisations have described the change as a step backwards that makes genuine accountability impossible.

The World of Knobble

Every summer, the Isle of Mull waits for a familiar visitor.

Knobble, a minke whale first identified in 2002, has become a local celebrity. He has appeared in children’s books, inspired a song, and even has his own Facebook page where residents share sighting updates. When Knobble’s tall dorsal fin, marked with its distinctive notch, breaks the surface of Tobermory Bay, word spreads fast. Tour boats adjust their routes. Families gather on the shoreline. For a few weeks, the island feels connected to something ancient and enormous.

Knobble is more than a tourist attraction. He represents decades of patient community science. The Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust (HWDT) has logged more than sixty confirmed sightings of him across the Inner Hebrides, making him one of the most well-documented individual minke whales in Europe.

“He is not simply a minke whale,” says Dr Lauren Hartny-Mills of HWDT. “He is this minke whale, with a specific history, a known range, and a relationship, however one-sided, with the human communities that celebrate his return.”

Minke whales are not solitary drifters. Research has documented individual personalities, site fidelity, and learned foraging strategies. They return to the same feeding grounds year after year, following routes that seem to be culturally transmitted across generations. They communicate through low-frequency calls that can travel hundreds of miles through the ocean. They remember.

When people watch Knobble surface, they are not observing an anonymous representative of a species. They are witnessing an individual life that has meaning, memory, and continuity. His story reveals something profound about our relationship with the sea. In Scotland, he is celebrated. In Norwegian waters, he could be killed.

The same animal that inspires books, songs, and science in one country can, a few hundred miles away, become a legal target for a grenade-tipped harpoon. This contradiction exposes the uneasy truth about migratory species and how arbitrary protection can be.

The Arbitrary Nature of Protection

Whales are managed under international law as if they were a fishery resource, subject to quotas and harvest regulations designed for species with rapid reproduction and high population turnover. Whales are not cod. They are long-lived, slow-reproducing, intelligent animals with complex social structures and individual identities.

“We are applying twentieth-century resource management frameworks to twenty-first-century understanding of animal sentience,” argues Dr Brakes. “The law has not caught up with the science.”

Scientific evidence shows that cetaceans display cultural transmission of knowledge, complex problem-solving, empathy, and even behaviours consistent with grief. These findings complicate the ethical calculus of whaling in ways that population numbers alone cannot capture.

Norway is a signatory to multiple international agreements on animal welfare and marine conservation. It presents itself as a leader on sustainability and enforces strong welfare laws for land animals. The question facing Norwegian policymakers is whether those same standards should extend to marine mammals and whether cultural tradition justifies practices that would be illegal on land.

Beyond Sentimentality: The Ecological Case

Knobble’s story is not only about compassion. It is also about function.

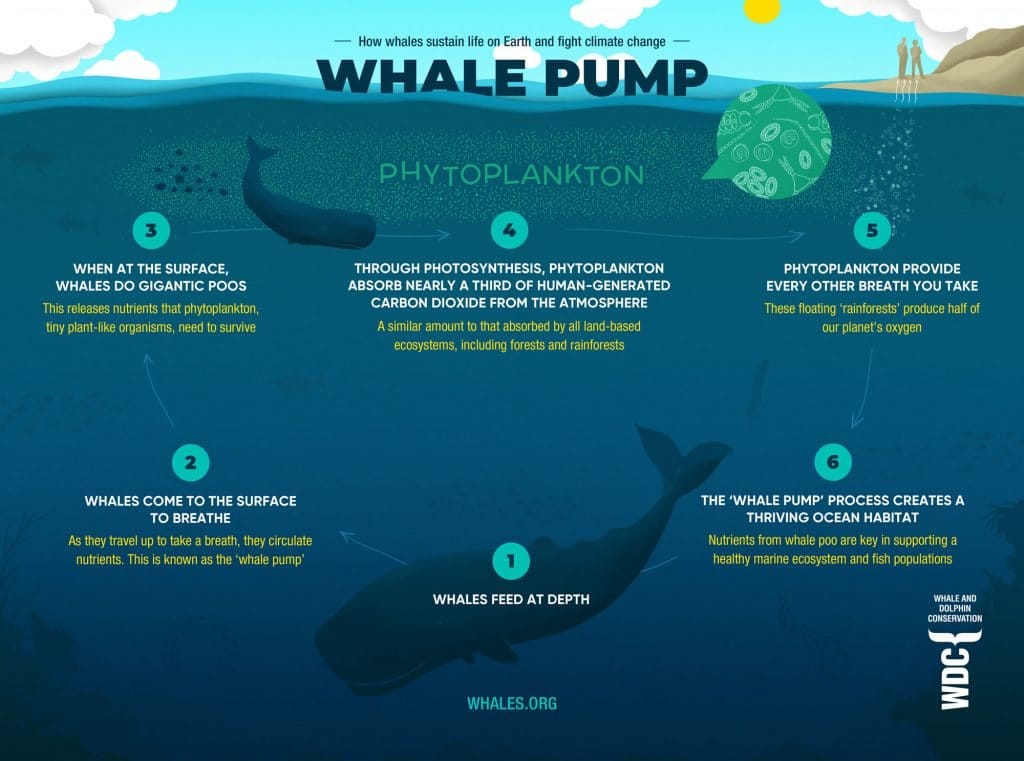

Whales are ecosystem engineers. When they dive to feed and return to the surface to breathe and defecate, they transport nutrients from the deep to the sunlit layers of the ocean. This “whale pump” fertilises phytoplankton blooms that form the base of the marine food web.

Phytoplankton perform roughly half of global photosynthesis, producing oxygen and absorbing carbon dioxide. An analysis by economists at the International Monetary Fund estimated that the climate and ecosystem value of a single great whale over its lifetime can exceed two million US dollars. Although the study focused on larger species, the principle applies across cetaceans. Living whales provide ecosystem services that dead whales cannot.

When whales die naturally, their bodies sink to the seabed, forming “whale falls” that sustain deep-sea ecosystems for decades. A single carcass can support hundreds of species. Killing whales removes these ecological functions. It disrupts nutrient cycling and reduces the ocean’s capacity to regulate climate.

“Every whale killed is a loss of planetary function,” says Dr Brakes. “We cannot build machines that replace what whales do for the Earth.”

The Economic Fiction

The economic case for Norwegian whaling has collapsed. Domestic consumption of whale meat is now extremely low. Surveys show that only about two percent of Norwegians eat whale meat regularly. Much of the catch ends up in cold storage, used for animal feed, or exported to Japan, where consumption is also declining.

The industry employs fewer than two hundred people and contributes almost nothing to Norway’s GDP.

By contrast, whale watching is a growing sector that generates billions of dollars globally each year and supports hundreds of jobs within Norway. The same whales killed for meat could generate far more income alive.

“The economics now favour protection,” says Dr Brakes. “This is not a trade-off between conservation and livelihoods. Protecting whales creates more value for both people and planet.”

Norwegian whaling persists not because of necessity or demand, but because the infrastructure remains, the quota exists, and political will has not yet caught up with public opinion.

Behind the Lens: How the Documentary was Made

Harpooned: The Great Whale Betrayal represents a new model for conservation documentation that combines field operations, legal expertise, and scientific rigour.

The ESPA team spent months planning the operation, consulting maritime lawyers to ensure they operated within international law. They used long-range lenses and drones to capture evidence without interference. Conditions were unpredictable, with sudden squalls and poor visibility. Each piece of footage was timestamped and GPS-tagged for evidential integrity.

“The conditions were brutal,” recalls Carr. “Arctic seas in summer are unpredictable. We had to maintain visual contact with whaling vessels while staying at a sufficient distance to avoid accusations of interference. Every shot you see in the film has coordinates and a timestamp. That is the standard of proof we needed.”

The team collaborated with Whale and Dolphin Conservation, which provided scientific guidance and welfare assessment protocols. After further analysis of all the footage has been assessed it will be submitted to Norwegian authorities as part of ongoing welfare investigations.

“Just because it is difficult does not mean it should be left alone,” says Carr. “This is conservation at the coalface. Someone has to bear witness.”

Their courage fills the gap left by governments unwilling or unable to monitor what happens beyond the horizon.

What Happens Next

Knobble will return to Scottish waters next summer, or he will not.

No one will know if his absence is temporary, a shift in migration, or permanent. No one will know if he swims safely through Norwegian waters or becomes one of the hundreds of whales killed under quota. That uncertainty makes his story so powerful. He exists between two worldviews: one that sees whales as individuals deserving of protection wherever they travel, and another that sees them as national resources to be managed and harvested.

Knobble’s migration route does not respect borders. The question for policymakers is whether protection should move with the whales or remain confined to territorial waters.

Public pressure has changed policy before. Iceland suspended whaling in 2023 on welfare grounds, then reissued a licence for 128 fin whales in 2024 under stricter rules. Japan withdrew from the International Whaling Commission in 2019 and resumed domestic whaling, although catches remain low due to lack of demand. Norway could choose a different path. The economic impact of ending whaling would be minimal. The welfare and ecological benefits would be profound.

“The hardest part,” says Carr, “is knowing that what we filmed is still legal. The cruelty is not hidden in the shadows of crime. It is written into policy.”

Political will is the missing ingredient.

A Being Worth Protecting

Knobble has never harmed anyone. He returns faithfully to Scottish shores each year, connecting human communities to something ancient and enduring. Whether he continues to do so depends on decisions made far from Tobermory Bay, in Norwegian fisheries ministries, in IWC meetings, and in the quiet calculations of policymakers balancing tradition against ethics.

The whales cannot speak in those rooms. We can.

A being that has never harmed us deserves better than betrayal.

Take action

Watch: Harpooned: The Great Whale Betrayal at speciesprotection.com

Support: Whale and Dolphin Conservation

Advocate: Contact your MP and urge the UK government to raise whaling welfare concerns at the next International Whaling Commission meeting.

Follow: Track Knobble’s sightings through HWDT’s Whale Track platform and contribute to citizen science.

Sources and References

Endangered Species Protection Agency (ESPA), Harpooned: The Great Whale Betrayal documentary materials, 2025.

Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC), “Norway’s Whaling Quota Raised to 1,406 Minke Whales,” 2025.

Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries, official quota and monitoring reports, 2022–2025.

NAMMCO (North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission) reports on whale killing methods and time-to-death data.

Egil Ole Øen patent filings and Norwegian media coverage of conflict-of-interest issues (Telegraph, 2023).

International Monetary Fund (Chami et al.), “Nature’s Solution to Climate Change,” 2019.

Roman et al., Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, “Whales as Marine Ecosystem Engineers,” 2014.

Deep-sea whale-fall research, Deep Sea Research Part II, 2019.

Norwegian School of Economics and Norstat surveys on whale-meat consumption, 2019–2020.

Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust (HWDT) photo-ID database and public materials on Knobble.

International Whaling Commission (IWC) meeting reports, 2019–2024.

Icelandic Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries licence announcements, 2024.

BBC News and Reuters coverage of Japanese and Icelandic whaling developments, 2019–2024.

My heart hurts.

I pray for a time when people will love animals so much, they won't be able to kill them.

Fascinating read! You’ve captured the complex history and cultural significance of whale hunting exceptionally well. As someone who has studied marine ecosystems and conservation policy, I really appreciate how you balanced the traditional practices with the modern ethical and ecological considerations. The discussion on sustainable alternatives and shifting global attitudes toward whale populations was particularly insightful. Looking forward to seeing more research-driven perspectives like this—it’s an important conversation that deserves nuanced voices like yours.