Green Water, Thin Whales

A monitoring gap in the Southern Ocean could mean we miss a food web collapse

Every summer, the great whales head south.

Antarctic blues, the largest animals ever to exist. Fin whales, sleek and fast. Humpbacks from breeding grounds as far away as Colombia and Tonga, swimming thousands of kilometres to converge on the same cold, krill-rich waters around South Georgia and the Scotia Sea.

They come because this is where the food is. Krill (small, shrimp-like crustaceans) swarm here in densities found almost nowhere else on Earth. A single blue whale can eat four tonnes of them in a day. The whales arrive lean from months of fasting. They leave fat, carrying the energy reserves that will fuel breeding, nursing, and the long migration home.

This system has worked for millions of years.

It depends on the photosynthetic efficiency of phytoplankton.

The Invisible Engine

Phytoplankton are microscopic. A single cell is smaller than the width of a human hair. There are trillions of them in every cubic kilometre of sunlit ocean. They do not look like much. They are the foundation of almost everything.

Around half of global photosynthetic oxygen production happens in the ocean, and phytoplankton do most of it. They also form the base of marine food webs. Phytoplankton feed zooplankton. Zooplankton feed krill. Krill feed whales. Cut the base of that chain and everything above it starves.

Here is what people often misunderstand about photosynthesis.

Sunlight does not automatically turn into oxygen.

Inside a cell, the energy has to be passed along correctly. Light is first caught by clusters of pigment molecules, like solar panels. These pass the energy to a smaller set of specialist sites called reaction centres. Only those centres can do the real work: splitting water, releasing oxygen, and making sugar.

If the handoff fails, nothing useful happens. The light is absorbed but wasted. It leaks away as heat or a faint glow. The cell saw the sunlight but could not use it.

It is like a relay race where the first runner sprints perfectly, then drops the baton. The effort was real. The race was lost.

Iron is what keeps the handoff working. Iron stress simply means that phytoplankton do not have enough iron to run photosynthesis efficiently.

Iron is a trace element. Cells need only tiny amounts of it, but without it, the proteins that move energy inside the cell cannot function properly.

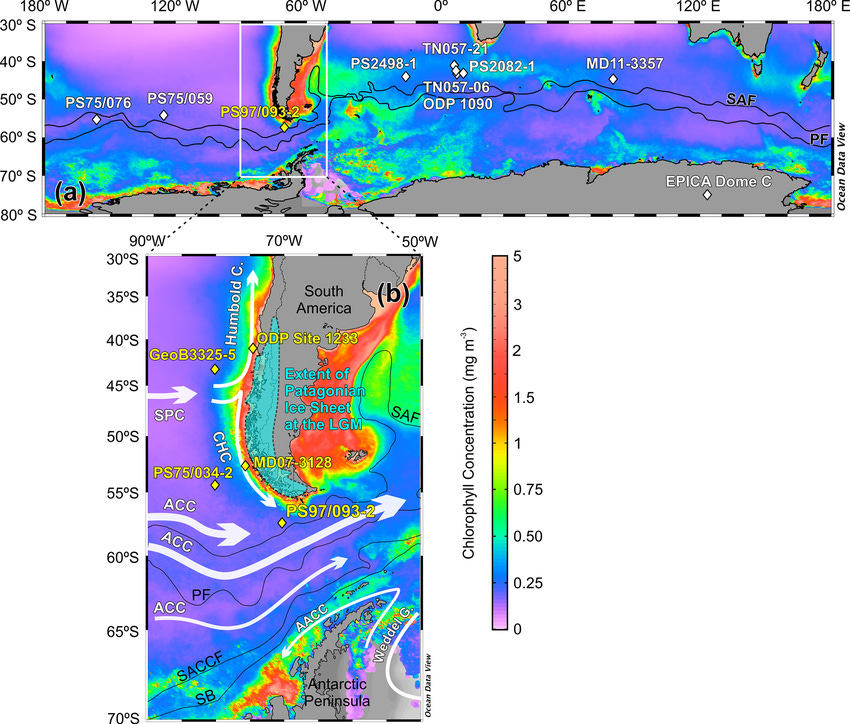

Large areas of the open ocean, including much of the Southern Ocean, are naturally low in iron. The metal is scarce in seawater and only enters from limited sources such as windblown dust, melting ice, or deep upwelling.

Iron sits inside the proteins that move energy from the light-catching pigments to the reaction centres. Without enough iron, the connection loosens. The baton gets dropped more often.

In iron-poor waters, the machinery still catches the light, but it cannot finish the job.

The Finding

A new paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences did something rarely attempted. It measured photosynthetic efficiency directly in wild phytoplankton communities, in the open ocean, under real conditions.

The team, led by Heshani Pupulewatte, with colleagues including Maxim Gorbunov, Tom Bibby, and Paul Falkowski, sailed from the South Atlantic into the Southern Ocean. They used fluorescence to see not just whether phytoplankton were there, but whether they were actually working.

The technique shows whether the light-catching parts of the cell are properly connected to the parts that do the chemistry. Whether the energy is being passed on and used, or leaking away as waste.

It is like checking not just that a factory has power, but whether the machines on the production line are actually running.

What they found is unsettling.

Under iron stress, up to about a quarter of the light-catching antennae in some phytoplankton were no longer connected to the reaction centres. Light reached the antennae, then had nowhere to go. The energy leaked away and was wasted.

The machinery was present. The wiring was loose.

When researchers added iron in controlled experiments, the system repaired itself within days. The connections tightened. Efficiency returned.

Iron stress does not switch photosynthesis off. It makes it inefficient.

The Southern Ocean, where krill swarm and whales feed, is one of the most iron-stressed regions on Earth.

The reason is geography and physics, not biology. The Southern Ocean is far from continents, so it receives very little wind-blown dust, the main natural source of iron to surface waters. Its cold surface layers are also strongly stratified, which limits the upward mixing of iron from deeper water. Climate change is intensifying both effects. Wind patterns are shifting, dust delivery is changing, and warming is strengthening stratification, making it harder for iron to reach the sunlit zone where phytoplankton live.

Why Efficiency Matters More Than Output

Here is an analogy that might help.

Think about two car engines. Both produce the same horsepower. One burns a litre of fuel to do it. The other burns two litres. From the outside, they look identical. Same speed. Same result.

One engine is healthy. The other is dying.

The inefficient engine is under stress. Its parts are wearing. Its systems are compensating. It will keep performing, right up until the moment it fails. The warning signs were there the whole time, hidden in a metric nobody was watching: how hard it had to work to deliver the same output.

The ocean works the same way.

Phytoplankton under iron stress can still photosynthesise. They can still produce oxygen. They can still show up on satellite images as green, productive water. They just have to burn more of their own energy to do it. Less is left over for growth. Less for reproduction. Less for building the biomass that feeds the next level of the food chain.

From space, the ocean looks fine. The chlorophyll is there. The productivity numbers look normal.

Underneath, the system is working harder for the same result, and that stress does not stay at the bottom of the food web. It propagates upward.

What follows is for paid subscribers: original reporting on the food web connection nobody is monitoring, the fishery management gap it creates, and the formal question I have now put to CCAMLR on the record.