Did Norway Just Save the Arctic Deep Sea? Here’s Why That Matters for Whales.

At WDC, we’ve been researching exactly why this industry poses such a threat to cetaceans. What we found should concern everyone.

On 3rd December 2025, Norway’s Labour government announced it would not issue a single deep-sea mining licence until at least 2029. The government will also cut all public funding for seabed mineral mapping.

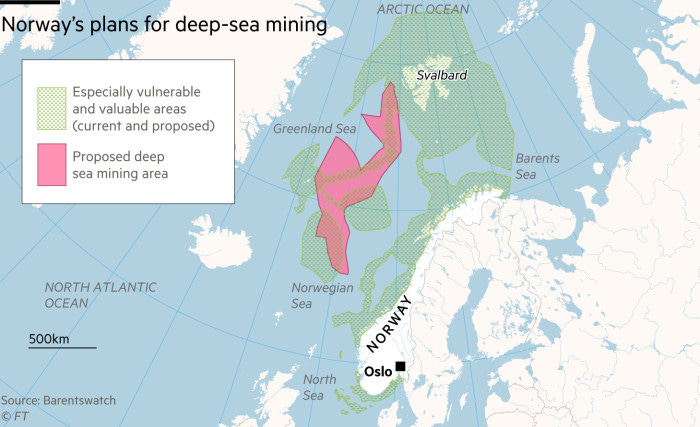

This is enormous. Norway was, until very recently, the world’s most aggressive proponent of ripping up the ocean floor. In January 2024, it became the first country to formally approve deep-sea mining in its national waters. The plan was to open 280,000 square kilometres of Arctic seabed for mineral extraction. Licences were expected this year.

That timeline has now collapsed. After intense negotiations between Labour and four opposition parties, the entire programme is on hold for at least four years.

At Whale and Dolphin Conservation, we have just completed a comprehensive scientific review of how underwater noise affects whales, dolphins, and porpoises. We worked with researchers at the Scottish Association for Marine Science to examine every major source of human-made noise in the ocean, from shipping to pile driving to military sonar. We also looked at emerging industries that barely exist yet but could reshape the ocean soundscape in the coming decades.

Deep-sea mining is one of those industries. What we found should make anyone who cares about marine life deeply uncomfortable.

Why Sound Matters

To understand why deep-sea mining threatens whales, you need to understand something fundamental about how the ocean works.

Light does not travel far underwater. Below about 200 metres, the ocean is essentially dark. Below 1,000 metres, it is pitch black. Whales that live and hunt in these depths cannot rely on their eyes. They rely on their ears.

Sound behaves very differently underwater than it does in air. It travels faster (about four times faster) and it travels much, much farther. A whale’s call can cross an entire ocean basin. This is not a quirk of whale biology. It is physics. The ocean is an extraordinarily efficient medium for transmitting sound.

Whales have evolved to exploit this. They use sound for everything: finding food, navigating across thousands of miles, locating mates, keeping track of their young, and maintaining the complex social bonds that define their lives. Toothed whales like sperm whales and beaked whales use echolocation, sending out clicks and listening for the echoes that bounce back from prey or obstacles. Baleen whales like humpbacks and blue whales produce songs that can travel for hundreds of kilometres.

When we talk about noise pollution in the ocean, we are not talking about annoyance. We are talking about sensory disruption at the most fundamental level. Imagine trying to have a conversation, find your family, or navigate to work while someone blasts an air horn in your ear, constantly, for months or years at a time. That is what chronic industrial noise does to whales.

The Secret Sound Highway

Here is something most people do not know. The deep ocean contains a natural acoustic channel that can carry sound across extraordinary distances.

It is called the SOFAR channel (Sound Fixing and Ranging channel), and it sits roughly between 600 and 1,200 metres deep in most of the world’s oceans. At this depth, a combination of temperature and pressure creates a layer where sound travels at its slowest speed. When sound enters this layer, it gets trapped. Instead of spreading out and dissipating, it bounces along inside the channel, travelling hundreds or even thousands of kilometres before losing energy.

Whales know about this channel. Many deep-diving species use it to communicate over vast distances. A whale in one part of the ocean can potentially be heard by another whale on the other side of an ocean basin.

Deep-sea mining would operate at exactly these depths. The equipment on the seabed, the riser pipes carrying material to the surface, the processing vessels above: all of this generates noise throughout the entire water column. Some of that noise would enter the SOFAR channel and propagate across distances we can barely comprehend.

Our review found that mining noise at depths greater than 1,000 metres could ‘ensonify vast oceanic regions.’ That is scientific language for: the sound could spread everywhere. Communication that has worked for millions of years could suddenly become impossible.

What Norway Was Planning

The area Norway wanted to mine sits on the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge, between Svalbard, Greenland, and Iceland. This is one of the most remote marine environments on Earth. It is also home to whales.

Research published last year found that 10 species of cetacean regularly inhabit this region. These include sperm whales, northern bottlenose whales, and several species of beaked whale. These are deep-diving specialists. Sperm whales routinely reach 2,000 metres. Beaked whales have been recorded at nearly 3,000 metres, the deepest dive of any mammal. They spend their lives in exactly the waters that mining would industrialise.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific, another major target for deep-sea mining, is even more biodiverse. Scientists have documented up to 30 cetacean species there, including dolphins, sperm whales, and various beaked whales.

Norway argued that accessing seabed minerals would help fund a ‘green transition’ away from oil and gas. The nodules on the ocean floor contain cobalt, manganese, and other metals used in batteries for electric vehicles. Mining companies framed this as environmentally responsible, a cleaner alternative to digging mines on land.

This argument has always been flawed. A report from the Environmental Justice Foundation found that deep-sea mining is not necessary for the clean energy transition. Improvements in technology, recycling, and circular economy practices could reduce demand for these minerals by 58 per cent by 2050. We do not need to destroy the ocean floor to build electric cars.

The Norwegian Environment Agency agreed. It concluded that moving forward with deep-sea mining was neither ‘environmentally responsible nor legally defensible.’ The Institute of Marine Research highlighted massive knowledge gaps about Arctic deep-sea ecosystems.

The government pressed ahead anyway. In January 2024, the Norwegian parliament voted 80 to 20 to approve mining. Only intense political pressure over the following months forced this week’s reversal.

What Mining Sounds Like

Let me be specific about what deep-sea mining involves, because the scale of the noise is hard to grasp without concrete details.

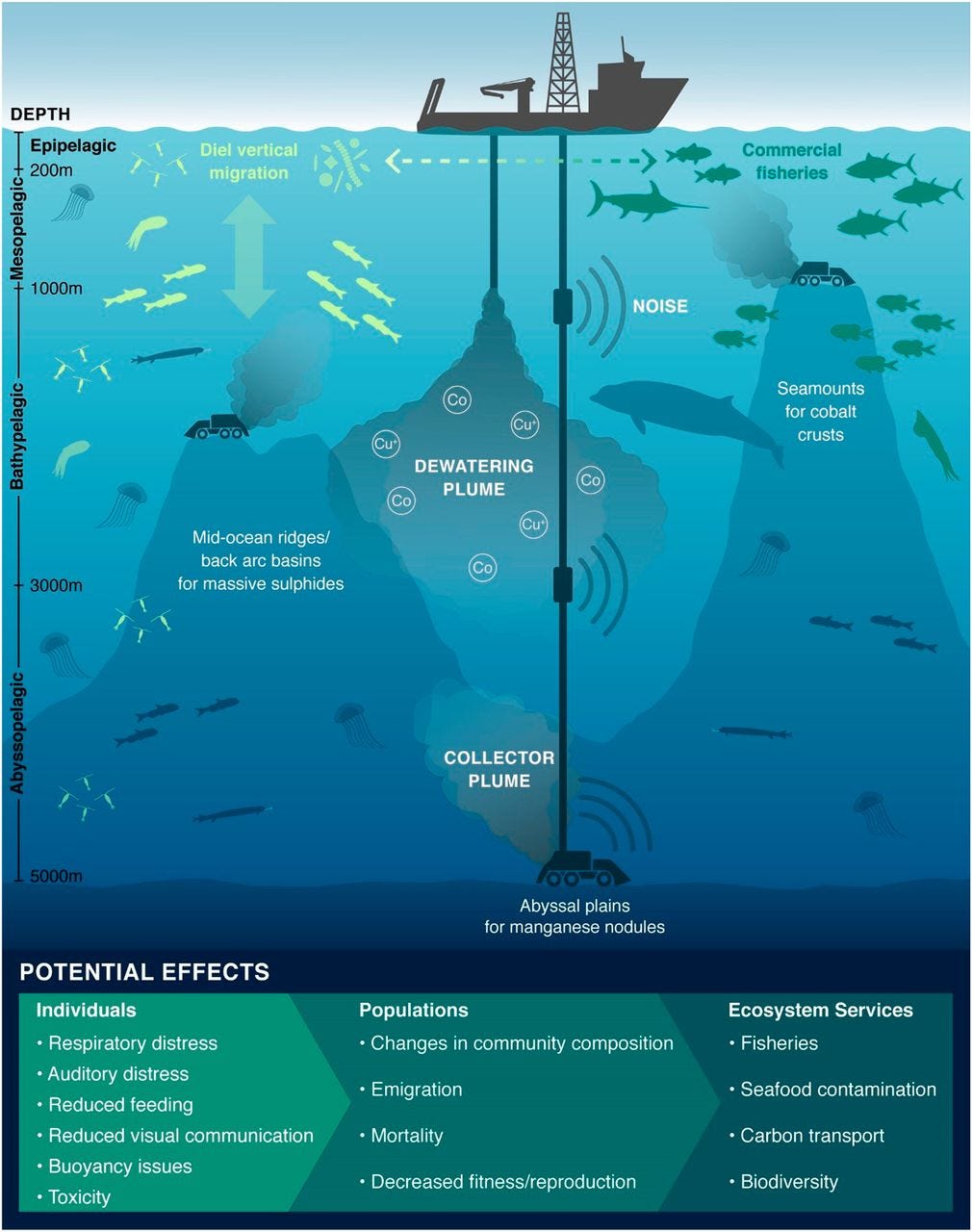

Our review compiled data on every stage of the mining process. During exploration, companies use sonar systems and seismic surveys to map the seabed. Some of these produce source levels up to 259 decibels. For context, a jet engine at close range is about 140 decibels. The decibel scale is logarithmic, meaning each 10-decibel increase represents a tenfold increase in sound intensity. These are extraordinarily loud sounds being pumped into an environment that has been essentially silent for millions of years.

During extraction, collector vehicles on the seabed scrape up nodules and sediment. Pumps and dredging equipment operate continuously. The material gets sucked up through riser pipes to processing vessels on the surface. Every part of this system generates noise: the collectors (up to 192 decibels), the cutting and drilling equipment (185 to 195 decibels) and the dynamic positioning systems that keep the surface vessels in place (180 to 197 decibels).

Commercial-scale mining would run 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for years. The noise would be continuous. There would be no quiet period, no recovery time, no escape.

For whales, this creates a problem called ‘masking.’ Their calls get drowned out. They cannot hear each other. Social bonds break down. Mothers lose contact with calves. Males cannot find females during breeding season. Navigation becomes unreliable. Hunting becomes harder.

The species most at risk are the deep-diving specialists: beaked whales, sperm whales, Risso’s dolphins. These animals are already known to be extremely sensitive to underwater noise. Beaked whales have mass-stranded following exposure to military sonar. They seem to panic, surfacing too quickly, developing something like the bends. We do not know exactly why they are so vulnerable, but we know they are.

Consider what we know about chronic noise exposure in whales more generally. Studies have shown that prolonged exposure to industrial noise causes elevated stress hormones. Researchers examining North Atlantic right whales after the shipping reduction following 11th September 2001 found that stress hormone levels dropped significantly within days. The ocean got quieter, and the whales became measurably calmer.

Mining would do the opposite. It would introduce constant industrial noise into waters that have been quiet for millions of years. Whales would have no escape. Unlike shipping lanes, which animals can learn to avoid, mining operations would occupy fixed locations for decades. Animals that have used particular feeding grounds for generations would face a choice: tolerate the noise or abandon the area entirely.

Neither option is good. Tolerating chronic noise comes with physiological costs: stress, reduced fertility, weakened immune systems. Abandoning feeding grounds means travelling farther for food, burning energy reserves, and potentially competing with other populations for resources. For species already under pressure from climate change, these additional stresses could push populations toward decline.

We Do Not Know What We Would Be Destroying

Here is what keeps me awake at night. We have barely begun to study the deep ocean. Scientists have explored less than one per cent of it. We know more about the surface of Mars than we know about the seabed a few hundred kilometres off our own coastlines.

The species that live in deep-sea mining areas remain, in scientific terms, ‘understudied.’ We lack ‘sufficient baseline demographic data to allow assessment of potential impacts.’ We do not know how many whales use these waters, when they use them, or what they use them for. We cannot assess what we would lose because we do not know what is there.

This is not a knowledge gap we can fill quickly. Cetaceans are long-lived animals with slow reproductive rates. Some whales live for over a century. Understanding their population dynamics requires decades of observation. Deep-sea ecosystems are even harder to study, requiring expensive equipment and ship time that few research programmes can afford.

If mining begins before this research happens, we will be conducting an uncontrolled experiment on one of the last wild places on Earth. We will not know what we have destroyed until it is too late to save it.

Professor Ben Wilson, who wrote the foreword to our report, put it clearly. Deep-sea mining would ‘add new noise pollution to previously relatively pristine far offshore cetacean habitats.’ These are places where the soundscape has remained essentially unchanged for millions of years. Industrial noise would transform them utterly.

Why Norway’s Decision Matters

Nearly 1,000 scientists and marine policy experts from over 70 countries have signed a statement calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining. More than 30 countries, including the UK and most EU member states, have publicly supported a pause. Portugal has legislated a moratorium until 2050.

Norway was the outlier. It was the country pushing hardest to make mining happen. Its decision to step back removes the most powerful advocate for rapid industrialisation of the deep ocean.

The International Seabed Authority, the UN body responsible for regulating mining in international waters, has been trying to finalise a ‘Mining Code’ that would govern commercial operations. It has repeatedly failed to reach agreement. Every delay makes it harder for the industry to build momentum.

This is how environmental campaigns are won. Not with a single dramatic moment, but with sustained pressure that gradually closes off options. Every country that joins the moratorium makes it harder for companies to find somewhere willing to host their operations. Every year of delay allows more research to accumulate, more public awareness to build, more political opposition to solidify.

Norway’s Prime Minister was careful to call this a ‘postponement’ rather than a permanent ban. He noted that the parties that forced this decision will not hold power forever. The mining industry has not gone away. The pressure to access seabed minerals will continue.

The victory happened because of how Norwegian politics works. The Labour government does not have a majority on its own. To pass its 2026 budget, it needed support from smaller parties: the Socialist Left Party, the Green Party, the Red Party, and the Centre Party. These parties made deep-sea mining a red line. No pause on mining, no budget agreement.

This is important because it shows what is possible. A year ago, mining in Norwegian waters seemed inevitable. The government had the votes. The industry had the momentum. Environmental groups were told they were fighting a losing battle.

They fought anyway. Greenpeace ran an international campaign. WWF Norway lobbied relentlessly. Scientists published research documenting the risks. Public opinion shifted. When budget negotiations came around, the opposition parties had the leverage they needed.

Haldis Tjeldflaat Helle of Greenpeace Nordic called the announcement ‘the nail in the coffin’ for deep-sea mining in Norway. WWF described it as ‘historic.’ I think they may be right, though the coffin is not yet buried. The industry will try again when political conditions change.

The next four years matter enormously. They offer a window to strengthen international protections, conduct the research we desperately need, and shift the political consensus permanently against deep-sea mining.

What Happens Now

At WDC, we are calling for the UK government to go further than Norway. We want to see Britain join the countries demanding a global moratorium, not just a national pause. We want the International Seabed Authority to halt progress on the Mining Code until adequate baseline data exists on the species and ecosystems at risk.

We also want to see noise recognised as the serious pollutant it is. Unlike plastic or chemical contamination, noise disappears the moment you stop making it. If we choose not to mine the deep ocean, the soundscape recovers immediately. The whales can hear each other again. The damage is not permanent, as long as we stop before it starts.

Norway has shown that political pressure works. A year ago, mining seemed inevitable. Today, it is on hold indefinitely. The government that championed this industry has been forced to abandon it, at least for now.

This happened because environmental groups refused to let the issue drop. Because scientists spoke out about the risks. Because opposition parties made it a condition of budget negotiations. Because ordinary people made clear that they cared about the deep ocean even if they would never see it.

The deep sea is the last great wilderness on Earth. It is home to species we have not yet discovered, ecosystems we barely understand, acoustic environments that have remained unchanged since before humans existed. We have a choice about whether to industrialise it for minerals we do not actually need.

Norway just made the right choice. The rest of the world needs to follow.

WDC’s report ‘Towards Quieter Seas: A Review of Anthropogenic Noise and Recommendations for Reducing Its Impacts on Cetaceans’ was published in September 2025 in collaboration with SAMS Enterprise.

If you found this article useful, please share it. The more people who understand what is at stake, the harder it becomes for politicians to ignore.

When people think about harm to the oceans I’m sure that noise pollution is very low in the list. Great article, Luke!

Thank you for the depth & education of this article. It’s in understanding the ‘why’ actions must be considered that people may begin to listen. I appreciate your insight deeply into this critical moment in history.